Nitric oxide & Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia; not so safe after all?

As a young resident I have a vivid memory of a baby with CDH having saturations of 60 – 65% despite HFOV, paralysis and alkalinization (yes we used to do that). It was at that time that I pretty much threw my hands in the air and declared there was really nothing left that we could do. One of my mentors, a very wise Neonatologist Dr. Henrique Rigatto looked at me and said “why don’t we try inhaled nitric oxide?” Being the resident immersed in the burgeoning field of evidence based medicine I questioned him on this stating “But the evidence shows no benefit of iNO in CDH in any trials”. He looked back at me and asked “Are you prepared to let this baby die without even trying it?”. When put that way I answered shyly that I would order the iNO and… it worked. Whether it was coincidence or not I cannot say but I felt he had a point which I have shared many times with students over the years. A drug may not show a benefit in a clinical RCT so at a population level it should not be our ” go to” drug of choice but on an individual level as a last resort sometimes these medications for an individual patient may make a difference. Looking at it from a different standpoint one might say it falls into the “can’t hurt but might help” category of therapy.

Or is it safe in CDH?

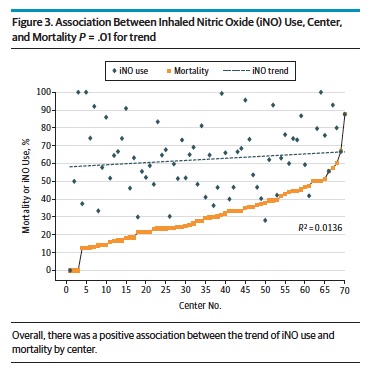

The Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group (CDHSG) of which we are a contributing centre recently published a retrospective analysis of the registry (now including over 9000 patients!) in an attempt to answer whether iNO use in babies with CDH is indeed safe. Evaluation of Variability in Inhaled Nitric Oxide Use and Pulmonary Hypertension in Patients With Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia.

The study looked at 2047 patients treated with iNO most of whom received 20 ppm of iNO. Interestingly about 15% of the patients treated with iNO did not have pulonary hypertension on ECHO.  The study found a positive association between centres using iNO and mortality. Moreover as the number of centres increased over time that used iNO so did the overall mortality in the study cohort. Beyond just looking at the trend in mortality with increasing use the authors took this one step further and used the statistical technique of propensity scoring to determine the attributable risk to mortality of using iNO in patients with CDH.

The study found a positive association between centres using iNO and mortality. Moreover as the number of centres increased over time that used iNO so did the overall mortality in the study cohort. Beyond just looking at the trend in mortality with increasing use the authors took this one step further and used the statistical technique of propensity scoring to determine the attributable risk to mortality of using iNO in patients with CDH.

Propensity scoring is an interesting technique that one can use to estimate risk when it is unlikely that a randomized controlled trial will be available and this is one of those cases. The technique uses an approach which strives to balance the variables that determined why different patients received a treatment so when comparing the outcomes of the two groups you manage to isolate the effect to just the treatment that is being studied. In this case the technique indicates that the estimate of harm is estimated to be 15% meaning that there is an estimated 15% increase in mortality for patients with CDH treated with iNO regardless of the indication.

So what to do with our next patient?

I can’t help but think back to the words of one of my mentors and ask myself what I would do if I was confronted with a patient who had CDH and was saturating poorly. I think what this study adds perhaps is that one should tread carefully with iNO in the setting of CDH. Maybe the overall message is that one should not jump to use iNO early in treatment. Optimizing ventilation, use of analgesics and sedation and even paralysis may be a better approach to controlling oxygenation than early iNO. When all those have been tried though and the patient is still not responding I think those wise words from long ago carry a lot of weight. “Are you prepared to let this baby die without even trying it?”

When mortality is already a strong possibility I believe at least for me the answer will remain no. I think it is important to keep iNO in your back pocket but to let a patient die without trying would leave me forever asking “what if”. That is a question I am certainly not comfortable asking at all.

As I cruised down the road with the wheel automatically turning with the curves in the road and the car speeding up or slowing down based on traffic and speed limit notices I couldn’t help but think of how such technology could be applied to medicine. How far away could the self driving ventilator or CPAP device be from development?

As I cruised down the road with the wheel automatically turning with the curves in the road and the car speeding up or slowing down based on traffic and speed limit notices I couldn’t help but think of how such technology could be applied to medicine. How far away could the self driving ventilator or CPAP device be from development?