Intubation is not an easy skill to maintain with the declining opportunities that exist as we move more and more to supporting neonates with CPAP. In the tertiary centres this is true and even more so in rural centres or non academic sites where the number of deliveries are lower and the number of infants born before 37 weeks gestational age even smaller. If you are a practitioner working in such a centre you may relate to the following scenario. A woman comes in unexpectedly at 33 weeks gestational age and is in active labour. She is assessed and found to be 8 cm and is too far along to transport. The provider calls for support but there will be an estimated two hours for a team to arrive to retrieve the infant who is about to be born. The baby is born 30 minutes later and develops significant respiratory distress. There is a t-piece resuscitator available but despite application the baby needs 40% oxygen and continues to work hard to breathe. A call is made to the transport team who asks if you can intubate and give surfactant. Your reply is that you haven’t intubated in quite some time and aren’t sure if you can do it. It is in this scenario that the following strategy might be helpful.

Surfactant Administration Through and Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA)

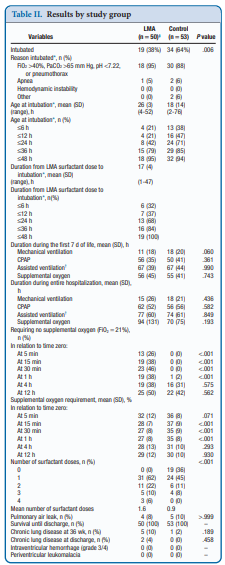

Use of an LMA has been taught for years in NRP now as a good choice to support ventilation when one can’t intubate. The device is easy enough to insert and given that it has a central lumen through which gases are exchanged it provides a means by which surfactant could be instilled through a catheter placed down the lumen of the device. Roberts KD et al published an interesting unmasked but randomized study on this topic Laryngeal Mask Airway for Surfactant Administration in Neonates: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Due to size limitations (ELBWs are too small to use this in using LMA devices) the eligible infants included those from 28 0/7 to 35 6/7 weeks and ≥1250 g. The infants needed to all be on CPAP +6 first and then fell into one of two treatment groups based on the following inclusion criteria: age ≤36 hours,

(FiO2) 0.30-0.40 for ≥30 minutes (target SpO2 88% and 92%), and chest radiograph and clinical presentation consistent with RDS.

Exclusion criteria included prior mechanical ventilation or surfactant administration, major congenital anomalies, abnormality of the airway, respiratory distress because of an etiology other than RDS, or an Apgar score <5 at 5 minutes of age.

Procedure & Primary Outcome

After the LMA was placed a y-connector was attached to the proximal end. On one side a CO2 detector was placed and then a bag valve mask in order to provide manual breaths and confirm placement over the airway. The other port was used to advance a catheter and administer curosurf in 2 mL aliquots. Prior to and then at the conclusion of the procedure the stomach contents were aspirated and the amount of surfactant determined to provide an estimate of how much surfactant was delivered to the lungs. The primary outcome was treatment failure necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilation in the first 7 days of life. Treatment failure was defined upfront and required 2 of the following: (1) FiO2 >0.40 for >30

minutes (to maintain SpO2 between 88% and 92%), (2) PCO2 >65 mmHg on arterial or capillary blood gas or >70 on venous blood gas, or (3) pH <7.22 or 1 of the following: (1) recurrent or severe apnea, (2) hemodynamic instability requiring pressors, (3) repeat surfactant dose, or (4) deemed necessary by medical provider.

Did it work?

It actually did. Of the 103 patients enrolled (50 LMA and 53 control) 38% required intubation in the LMA group vs 64% in the control arm. The authors did not reach their desired enrollment based on their power calculation but that is ok given that they found a difference. What is really interesting is that they found a difference in the clinical end point despite many infants clearly not receiving a full dose of surfactant as measured by gastric aspirate. Roughly 25% of the infants were found to have not received any surfactant, 20% had >50% of the dose in the stomach and the other 50+% had < 10% of the dose in the stomach meaning that the majority was in fact deposited in the lungs. I suppose it shouldn’t come as a surprise that among the secondary outcomes the duration length of mechanical ventilation did not differ between two groups which I presume occurred due to the babies needing intubation being similar. If you needed it you needed it so to speak. Further evidence though of the effectiveness of the therapy was that the average FiO2 30 minutes after being treated was significantly lower in the group with the LMA treatment 27 vs 35%. What would have been interesting to see is if you excluded the patients who received little or no surfactant, how did the ones treated with intratracheal deposition of the dose fare? One nice thing to see though was the lack of harm as evidenced by no increased rate of pneumothorax, prolonged ventilation or higher oxygen.

Should we do this routinely?

There was a 26% reduction in intubations in te LMA group which if we take this as the absolute risk reduction means that for every 4 patients treated with an LMA surfactant approach, one patient will avoid intubation. That is pretty darn good! If we also take into account that in the real world, if we thought that little of the surfactant entered the lung we would reapply the mask and try the treatment again. Even if we didn’t do it right away we might do it hours later.

In a tertiary care centre, this approach may not be needed as a primary method. If you fail to intubate though for surfactant this might well be a safe approach to try while waiting for a more definitive airway. Importantly this won’t help you below 28 weeks or 1250g as the LMA is too small but with smaller LMAs might this be possible. Stay tuned as I suspect this is not the last we will hear of this strategy!

I am a retired NICU Nurse and always wished for surfactant to be somehow developed into a solution that could be given as a mist

Via inhaler/mask etc. That would eliminate the need to intubate in some cases.

Thanks for reviewing this interesting paper. Regarding the amount of surfactant delivered to the stomach, rather than 25% of infants not receiving any surfactant as you state, I read the paper as saying that 13/50 (26%) had no surfactant aspirated from the stomach (ie received 100% of the dose in the lungs). I think this accords with the observed reduction in FiO2 post-procedure.

good pick up!