by All Things Neonatal | Apr 1, 2018 | Neonatal, Neonatology, preemie, Prematurity, ventilation

For almost a decade now confirmation of intubation is to be done using detection of exhaled CO2. The 7th Edition of NRP has the following to say about confirmation of ETT placement “The primary methods of confirming endotracheal tube placement within the trachea are detecting exhaled CO2 and a rapidly rising heart rate.” They further acknowledge that there are two options for determining the presence of CO2 “There are 2 types of CO2 detectors available. Colorimetric devices change color in the presence of CO2. These are the most commonly used devices in the delivery room. Capnographs are electronic monitors that display the CO2 concentration with each breath.” The NRP program stops short of recommending one versus the other. I don’t have access to the costs of the colorimetric detectors but I would imagine they are MUCH cheaper than the equipment and sensors required to perform capnography using the NM3 monitor as an example. The real question though is if capnography is truly better and might change practice and create a safer resuscitation, is it the way to go?

Fast but not fast enough?

So we have a direct comparison to look at. Hunt KA st al published Detection of exhaled carbon dioxide following intubation during resuscitation at delivery this month. They started from the standpoint of knowing from the manufacturer of the Pedicap that it takes a partial pressure of CO2 of 4 mm Hg to begin seeing a colour change from purple to yellow but only when the CO2 reaches 15 mm Hg do you see a consistent colour change with that device. The capnograph from the NM3 monitor on the other hand is quantitative so is able to accurately display when those two thresholds are reached. This allowed the group to compare how long it took to see the first colour change compared to any detection of CO2 and then at the 4 and 15 mm Hg levels to see which is the quicker method of detection. It is an interesting question as what would happen if you were in a resuscitation and the person intubates and swears that they are in but there is no colour change for 5, 10 or 15 seconds or longer? At what point do you pull the ETT? Compare that with a quantitative method in which there is CO2 present but it is lower than 4. Would you leave the tube in and use more pressure (either PIP/PEEP or both?)? Before looking at the results, it will not shock you that ANY CO2 should be detected faster than two thresholds but does it make a difference to your resuscitation?

The Head to Head Comparison

The study was done retrospectively for 64 infants with a confirmed intubation using the NM3 monitor and capnography. Notably the centre did not use a colorimetric detector as a comparison group but rather relied on the manufacturers data indicating the 4 and 15 mm Hg thresholds for colour changes. The mean age of patients intubated was 27 weeks with a range of 23 – 34 weeks. The results I believe show something quite interesting and informative.

|

Median time secs (range) |

| Earliest CO2 detection |

3.7 (0 – 44s) |

| 4 mm Hg |

5.3 (0 – 727) |

| 15 mm Hg |

8.1 (0 – 727) |

I wouldn’t worry too much about a difference of 1.6 seconds to start getting a colour change but it is the range that has me a little worried. The vast majority of the patients demonstrated a level of 4 or 15 mm Hg within 50 seconds although many were found to take 25-50 seconds. When compared to a highest level of 44 seconds in the first detection of CO2 group it leads one to scratch their head. How many times have you been in a resuscitation and with no CO2 change you keep the ETT in past 25 seconds? Looking closer at the patients, there were 12 patients that took more than 30 seconds to reach a threshold of 4 mm Hg. All but one of the patients had a heart rate in between 60-85. Additionally there was an inverse relationship found between gestational age and time to detection. In other words, the smallest of the babies in the study took the longest to establish the threshold of 4 and 15 mm Hg.

Putting it into context?

What this study tells me is that the most fragile of infants may take the longest time to register a colour change using the colorimetric devices. It may well be that these infants take longer to open up their pulmonary vasculature and deliver CO2 to the alveoli. As well these same infants may take longer to open the lung and exhale the CO2. I suppose I worry that when a resuscitation is not going well and an infant at 25 weeks is bradycardic and being given PPV through an ETT without colour change, are they really not intubated? In our own centre we use capnometry in these infants (looks for a wave form of CO2) which may be the best option if you are looking to avoid purchasing equipment for quantitative CO2 measurements. I do worry though that in places where the colorimetric devices are used for all there will be patients who are extubated due to the thought that they in fact have an esophageal intubation when the truth is they just need time to get the CO2 high enough to register a change in colour.

Anyways, this is food for thought and a chance to look at your own practice and see if it is in need of a tweak…

by All Things Neonatal | Mar 14, 2018 | apnea of prematurity, caffeine, extubation, Neonatal, Neonatology, Prematurity, ventilation

Caffeine seems to be good for preterm infants. We know that it reduces the frequency of apnea in the this population and moreover facilitates weaning off the ventilator in a shorter time frame than if one never received it at all. The earlier you give it also seems to make a difference as shown in the Cochrane review on prophylactic caffeine. When given in such a fashion the chances of successful extubation increase. Less time on the ventilator not surprisingly leads to less chronic lung disease which is also a good thing.

I have written about caffeine more than once though so why is this post different? The question now seems to be how much caffeine is enough to get the best outcomes for our infants. Last month I wrote about the fact that as the half life of caffeine in the growing preterm infant shortens, our strategy in the NICU might be to change the dosing of caffeine as the patient ages. Some time ago though I wrote about the use of higher doses of caffeine and in the study analyzed warned that there had been a finding of increased cerebellar hemorrhage in the group randomized to receive the higher dosing. I don’t know about where you work but we are starting to see a trend towards using higher caffeine base dosing above 5 mg/kg/d. Essentially, we are at times “titrating to effect” with dosing being as high as 8-10 mg/kg/d of caffeine base.

Does it work to improve meaningful outcomes?

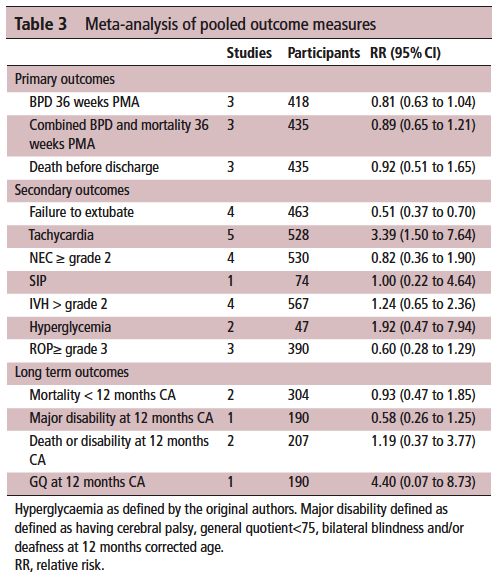

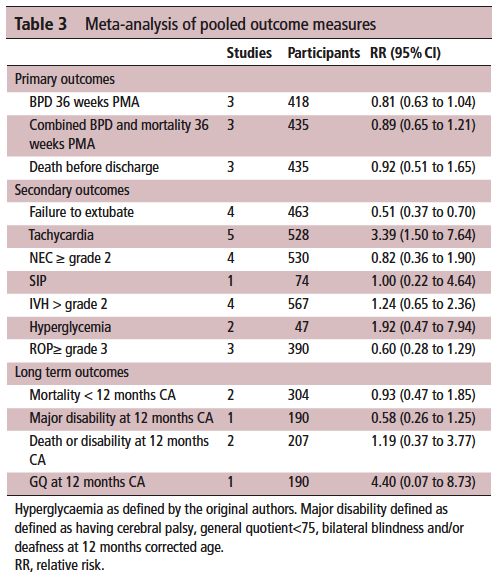

This month Vliegenthart R et al published a systematic review of all RCTs that compared a high vs low dosing strategy for caffeine in infants under 32 weeks at birth; High versus standard dose caffeine for apnoea: a systematic review. All told there were 6 studies that met the criteria for inclusion. Low dosing (all in caffeine base) was considered to be 5- 15 mg/kg with a maintenance dose of 2.5 mg/kg to 5 mg/kg. High dosing was a load of 5 mg/kg to 40 mg/kg with a maintenance of 2.5 mg/kg to 15 mg/kg. The variability in the dosing (some of which I would not consider high at all) makes the quality of the included studies questionable so a word of warning that the results may not truly be “high” vs “low” but rather “inconsistently high” vs. “inconsistently low”.

The results though may show some interesting findings that I think provide some reassurance that higher dosing can allow us to sleep at night.

On the positive front, while there was no benefit to BPD and mortality at 36 weeks PMA they did find if they looked only at those babies who were treated with caffeine greater than 14 days there was a statistically significant difference in both reduction of BPD and decreased risk of BPD and mortality. This makes quite a bit of sense if you think about it for a moment. If we know that caffeine improves the chances of successful extubation and we also know it reduces apnea, then who might be on caffeine for less than 2 weeks? The most stable of babies I would expect! These babies were all < 32 weeks at birth. What the review suggests is that those babies who needed caffeine for longer durations benefit the most from the higher dose. I think I can buy that.

On the adverse event side, I suppose it shouldn’t surprise many that the risk of tachycardia was statistically increased with an RR of 3.4. Anyone who has explored higher dosing would certainly buy that as a side effect that we probably didn’t need an RCT to prove to us. Never mind that, have you ever taken your own pulse after a couple strong coffees in the morning?

What did it not show?

It’s what the study didn’t show that is almost equally interesting. The cerebellar hemorrhages seen in the study I previously wrote about were not seen at all in the other studies. There could be a lesson in there about taking too much stock in secondary outcomes in small studies…

Also of note, looking at longer term outcome measures there appears to be no evidence of harm when the patients are all pooled together. The total number of patients in all of these studies was 620 which for a neonatal systematic review is not bad. A larger RCT may be needed to conclusively tell us what to do with a high and low dosing strategy that we can all agree on. What do we do though in the here and now? More specifically, if you are on call tomorrow and a baby is on 5 mg/kg/d of caffeine already, will you intubate them if they are having copious apneic events or give them a higher dose of caffeine when CPAP or NIPPV that they are already on isn’t cutting it? That is where the truth about how you feel about the evidence really comes out. These decisions are never easy but unfortunately you sometimes have to make a decision and the perfect study hasn’t been done yet. I am not sure where you sit on this but I think this study while certainly flawed gives me some comfort that nothing is truly standing out especially given the fact that some of the “high dose” studies were truly high. Will see what happens with my next patient!

by All Things Neonatal | Feb 28, 2018 | resuscitation, technology, ventilation

The lungs of a preterm infant are so fragile that over time pressure limited time cycled ventilation has given way to volume guaranteed (VG) or at least measured breaths. It really hasn’t been that long that this has been in vogue. As a fellow I moved from one program that only used VG modes to another program where VG may as well have been a four letter word. With time and some good research it has become evident that minimizing excessive tidal volumes by controlling the volume provided with each breath is the way to go in the NICU and was the subject of a Cochrane review entitled Volume-targeted versus pressure-limited ventilation in neonates. In case you missed it, the highlights are that neonates ventilated with volume instead of pressure limits had reduced rates of:

death or BPD

pneumothoraces

hypocarbia

severe cranial ultrasound pathologies

duration of ventilation

These are all outcomes that matter greatly but the question is would starting this approach earlier make an even bigger difference?

Volume Ventilation In The Delivery Room

I was taught a long time ago that overdistending the lungs of an ELBW in the first few breaths can make the difference between a baby who extubates quickly and one who goes onto have terribly scarred lungs and a reliance on ventilation for a protracted period of time. How do we ventilate the newborn though? Some use a self inflating bag, others an anaesthesia bag and still others a t-piece resuscitator. In each case one either attempts to deliver a PIP using the sensitivity of their hand or sets a pressure as with a t-piece resuscitator and hopes that the delivered volume gets into the lungs. The question though is how much are we giving when we do that?

High or Low – Does it make a difference to rates of IVH?

One of my favourite groups in Edmonton recently published the following paper; Impact of delivered tidal volume on the occurrence of intraventricular haemorrhage in preterm infants during positive pressure ventilation in the delivery room. This prospective study used a t-piece resuscitator with a flow sensor attached that was able to calculate the volume of each breath delivered over 120 seconds to babies born at < 29 weeks who required support for that duration. In each case the pressure was set at 24 for PIP and +6 for PEEP. The question on the authors’ minds was that all other things being equal (baseline characteristics of the two groups were the same) would 41 infants given a mean volume < 6 ml/kg have less IVH compared to the larger group of 124 with a mean Vt of > 6 ml/kg. Before getting into the results, the median numbers for each group were 5.3 and 8.7 mL/kg respectively for the low and high groups. The higher group having a median quite different from the mean suggests the distribution of values was skewed to the left meaning a greater number of babies were ventilated with lower values but that some ones with higher values dragged the median up.

Results

| IVH |

< 6 mL/kg |

> 6 ml/kg |

p |

| 1 |

5% |

48% |

|

| 2 |

2% |

13% |

|

| 3 |

0 |

5% |

|

| 4 |

5% |

35% |

|

| Grade 3 or 4 |

6% |

27% |

0.01 |

| All grades |

12% |

51% |

0.008 |

Let’s be fair though and acknowledge that much can happen from the time a patient leaves the delivery room until the time of their head ultrasounds. The authors did a reasonable job though of accounting for these things by looking at such variables as NIRS cerebral oxygenation readings, blood pressures, rates of prophylactic indomethacin use all of which might be expected to influence rates of IVH and none were different. The message regardless from this study is that excessive tidal volume delivered after delivery is likely harmful. The problem now is what to do about it?

The Quandary

Unless I am mistaken, there isn’t a volume regulated bag-mask device that we can turn to for control of delivered tidal volume. Given that all the babies were treated the same with the same pressures I have to believe that the babies with stiffer lungs responded less in terms of lung expansion so in essence the worse the baby, the better they did in the long run at least from the IVH standpoint. The babies with the more compliant lungs may have suffered from being “too good”. Getting a good seal and providing good breathes with a BVM takes a lot of skill and practice. This is why the t-piece resuscitator grew in popularity so quickly. If you can turn a couple of dials and place it over the mouth and nose of a baby you can ventilate a newborn. The challenge though is that there is no feedback. How much volume are you giving when you start with the same settings for everyone? What may seem easy is actually quite complicated in terms of knowing what we are truly delivering to the patient. I would put to you that someone far smarter than I needs to develop a commercially available BVM device with real-time feedback on delivered volume rather than pressure. Being able to adjust our pressure settings whether they be manual or set on a device is needed and fast!

Perhaps someone reading this might whisper in the ear of an engineer somewhere and figure out how to do this in a device that is low enough cost for everyday use.

by All Things Neonatal | Dec 28, 2017 | preemie, Prematurity, technology, ventilation

Intubation is not an easy skill to maintain with the declining opportunities that exist as we move more and more to supporting neonates with CPAP. In the tertiary centres this is true and even more so in rural centres or non academic sites where the number of deliveries are lower and the number of infants born before 37 weeks gestational age even smaller. If you are a practitioner working in such a centre you may relate to the following scenario. A woman comes in unexpectedly at 33 weeks gestational age and is in active labour. She is assessed and found to be 8 cm and is too far along to transport. The provider calls for support but there will be an estimated two hours for a team to arrive to retrieve the infant who is about to be born. The baby is born 30 minutes later and develops significant respiratory distress. There is a t-piece resuscitator available but despite application the baby needs 40% oxygen and continues to work hard to breathe. A call is made to the transport team who asks if you can intubate and give surfactant. Your reply is that you haven’t intubated in quite some time and aren’t sure if you can do it. It is in this scenario that the following strategy might be helpful.

Surfactant Administration Through and Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA)

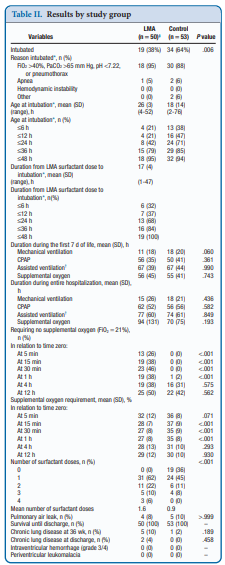

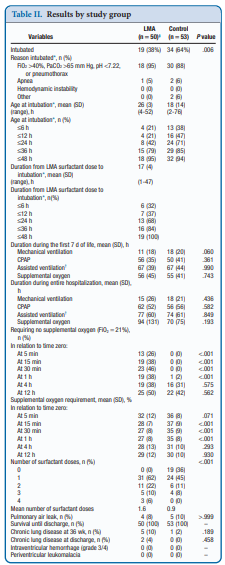

Use of an LMA has been taught for years in NRP now as a good choice to support ventilation when one can’t intubate. The device is easy enough to insert and given that it has a central lumen through which gases are exchanged it provides a means by which surfactant could be instilled through a catheter placed down the lumen of the device. Roberts KD et al published an interesting unmasked but randomized study on this topic Laryngeal Mask Airway for Surfactant Administration in Neonates: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Due to size limitations (ELBWs are too small to use this in using LMA devices) the eligible infants included those from 28 0/7 to 35 6/7 weeks and ≥1250 g. The infants needed to all be on CPAP +6 first and then fell into one of two treatment groups based on the following inclusion criteria: age ≤36 hours,

(FiO2) 0.30-0.40 for ≥30 minutes (target SpO2 88% and 92%), and chest radiograph and clinical presentation consistent with RDS.

Exclusion criteria included prior mechanical ventilation or surfactant administration, major congenital anomalies, abnormality of the airway, respiratory distress because of an etiology other than RDS, or an Apgar score <5 at 5 minutes of age.

Procedure & Primary Outcome

After the LMA was placed a y-connector was attached to the proximal end. On one side a CO2 detector was placed and then a bag valve mask in order to provide manual breaths and confirm placement over the airway. The other port was used to advance a catheter and administer curosurf in 2 mL aliquots. Prior to and then at the conclusion of the procedure the stomach contents were aspirated and the amount of surfactant determined to provide an estimate of how much surfactant was delivered to the lungs. The primary outcome was treatment failure necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilation in the first 7 days of life. Treatment failure was defined upfront and required 2 of the following: (1) FiO2 >0.40 for >30

minutes (to maintain SpO2 between 88% and 92%), (2) PCO2 >65 mmHg on arterial or capillary blood gas or >70 on venous blood gas, or (3) pH <7.22 or 1 of the following: (1) recurrent or severe apnea, (2) hemodynamic instability requiring pressors, (3) repeat surfactant dose, or (4) deemed necessary by medical provider.

Did it work?

It actually did. Of the 103 patients enrolled (50 LMA and 53 control) 38% required intubation in the LMA group vs 64% in the control arm. The authors did not reach their desired enrollment based on their power calculation but that is ok given that they found a difference. What is really interesting is that they found a difference in the clinical end point despite many infants clearly not receiving a full dose of surfactant as measured by gastric aspirate. Roughly 25% of the infants were found to have not received any surfactant, 20% had >50% of the dose in the stomach and the other 50+% had < 10% of the dose in the stomach meaning that the majority was in fact deposited in the lungs. I suppose it shouldn’t come as a surprise that among the secondary outcomes the duration length of mechanical ventilation did not differ between two groups which I presume occurred due to the babies needing intubation being similar. If you needed it you needed it so to speak. Further evidence though of the effectiveness of the therapy was that the average FiO2 30 minutes after being treated was significantly lower in the group with the LMA treatment 27 vs 35%. What would have been interesting to see is if you excluded the patients who received little or no surfactant, how did the ones treated with intratracheal deposition of the dose fare? One nice thing to see though was the lack of harm as evidenced by no increased rate of pneumothorax, prolonged ventilation or higher oxygen.

Should we do this routinely?

There was a 26% reduction in intubations in te LMA group which if we take this as the absolute risk reduction means that for every 4 patients treated with an LMA surfactant approach, one patient will avoid intubation. That is pretty darn good! If we also take into account that in the real world, if we thought that little of the surfactant entered the lung we would reapply the mask and try the treatment again. Even if we didn’t do it right away we might do it hours later.

In a tertiary care centre, this approach may not be needed as a primary method. If you fail to intubate though for surfactant this might well be a safe approach to try while waiting for a more definitive airway. Importantly this won’t help you below 28 weeks or 1250g as the LMA is too small but with smaller LMAs might this be possible. Stay tuned as I suspect this is not the last we will hear of this strategy!

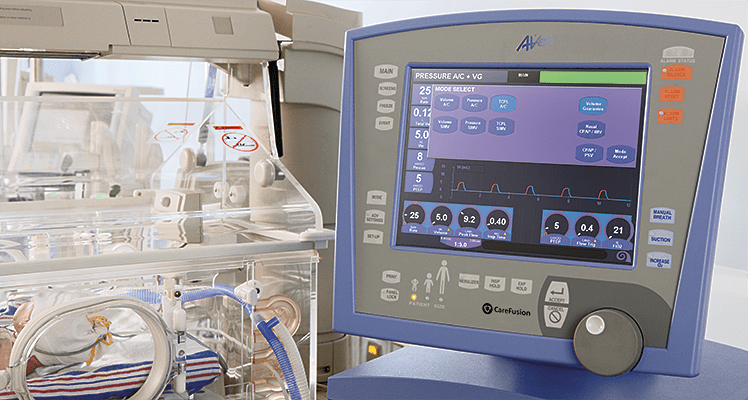

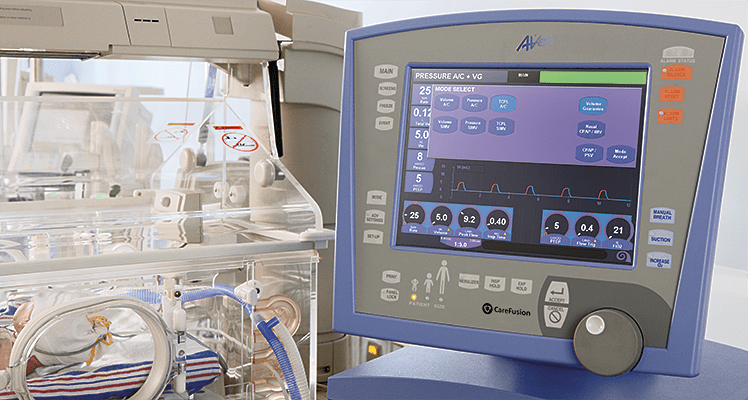

by All Things Neonatal | Oct 5, 2017 | Innovation, Neonatology, ventilation

It has been over two years since I have written on this subject and it continues to be something that I get excited about whenever a publication comes my way on the topic. The last time I looked at this topic it was after the publication of a randomized trial comparing in which one arm was provided automated FiO2 adjustments while on ventilatory support and the other by manual change. Automated adjustments of FiO2. Ready for prime time? In this post I concluded that the technology was promising but like many new strategies needed to be proven in the real world. The study that the post was based on examined a 24 hour period and while the results were indeed impressive it left one wondering whether longer periods of use would demonstrate the same results. Moreover, one also has to be wary of the Hawthorne Effect whereby the results during a study may be improved simply by being part of a study.

The Real World Demonstration

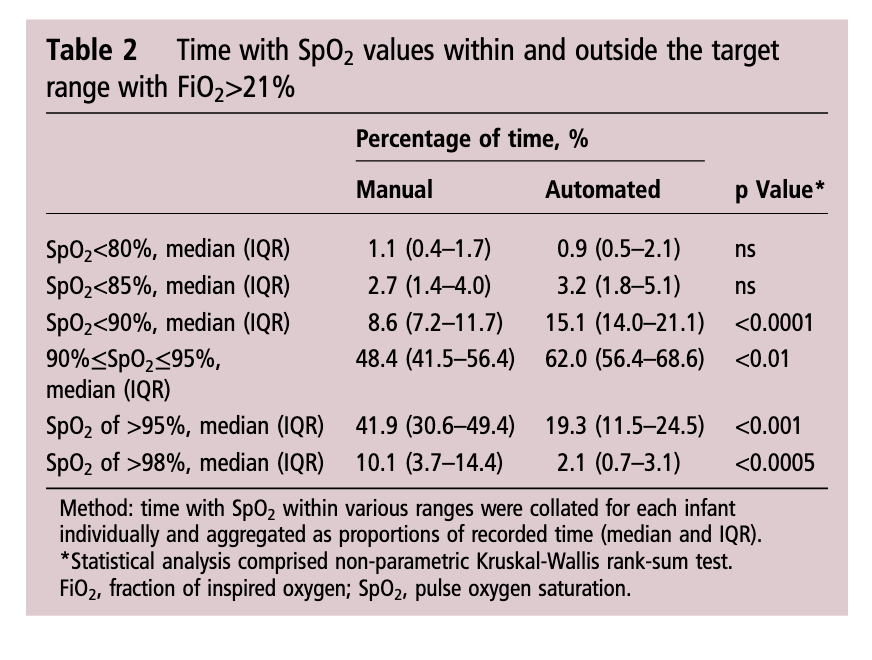

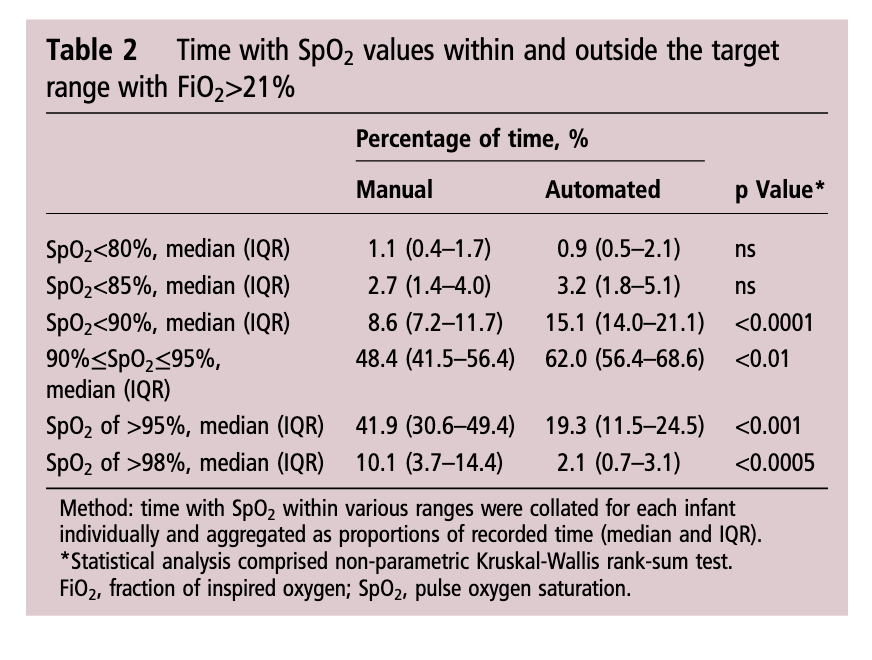

So the same group decided to look at this again but in this case did a before and after comparison. The study looked at a group of preterm infants under 30 weeks gestational age born from May – August 2015 and compared them to August to January 2016. The change in practice with the implementation of the CLiO2 system with the Avea ventilator occurred in August which allowed two groups to be looked at over a relatively short period of time with staff that would have seen little change before and after. The study in question is by Van Zanten HA The effect of implementing an automated oxygen control on oxygen saturation in preterm infants. For the study the target range of FiO2 for both time periods was 90 – 95% and the primary outcome was the percentage of time spent in this range. Secondary outcomes included time with FiO2 at > 95% (Hyperoxemia) and < 90, <85 and < 80% (hypoxemia). Data were collected when infants received respiratory support by the AVEA and onlyincluded for analysis when supplemental oxygen was given, until the infants reached a GA of 32 weeks

As you might expect since a computer was controlling the FiO2 using a feedback loop from the saturation monitor it would be a little more accurate and immediate in manipulating FiO2 than a bedside nurse who has many other tasks to manage during the care of an infant. As such the median saturation was right in the middle of the range at 93% when automated and 94% when manual control was used. Not much difference there but as was seen in the shorter 24 hour study, the distribution around the median was tighter with automation. Specifically with respect to ranges, hyperoxemia and hypoxemia the following was noted (first number is manual and second comparison automated in each case).

Time spent in target range: 48.4 (41.5–56.4)% vs 61.9 (48.5–72.3)%; p<0.01

Hyperoxemia >95%: 41.9 (30.6–49.4)% vs 19.3 (11.5–24.5)%; p<0.001

< 90%: 8.6 (7.2–11.7)% vs 15.1 (14.0–21.1)%;p<0.0001

< 85%: 2.7 (1.4–4.0)% vs 3.2 (1.8–5.1)%; ns

Hypoxemia < 80%: 1.1 (0.4–1.7)% vs 0.9 (0.5–2.1)%; ns

What does it all mean?

I find it quite interesting that while hyperoxemia is reduced, the incidence of saturations under 90% is increased with automation. I suspect the answer to this lies in the algorithmic control of the FiO2. With manual control the person at the bedside may turn up a patient (and leave them there a little while) who in particular has quite labile saturations which might explain the tendency towards higher oxygen saturations. This would have the effect of shifting the curve upwards and likely explains in part why the oxygen saturation median is slightly higher with manual control. With the algorithm in the CLiO2 there is likely a tendency to respond more gradually to changes in oxygen saturation so as not to overshoot and hyperoxygenate the patient. For a patient with labile oxygen saturations this would have a similar effect on the bottom end of the range such that patients might be expected to drift a little lower then the target of 90% as the automation corrects for the downward trend. This is supported by the fact that when you look at what is causing the increase in percentage of time below 90% it really is the category of 85-89%.

Is this safe? There will no doubt be people reading this that see the last line and immediately have flashbacks to the SUPPORT trial which created a great deal of stress in the scientific community when the patients in the 85-89% arm of the trial experienced higher than expected mortality. It remains unclear what the cause of this increased mortality was and in truth in our own unit we accept 88 – 92% as an acceptable range. I have no doubt there are units that in an attempt to lessen the rate of ROP may allow saturations to drop as low as 85% so I continue to think this strategy of using automation is a viable one.

For now the issue is one of a ventilator that is capable of doing this. If not for the ventilated patient at least for patients on CPAP. In our centre we don’t use the Avea model so that system is out. With the system we use for ventilation there is also no option. We are anxiously awaiting the availability of an automated system for our CPAP device. I hope to be able to share our own experience positively when that comes to the market. From my standpoint there is enough to do at the bedside. Having a reliable system to control the FiO2 and minimize oxidative stress is something that may make a real difference for the babies we care for and is something I am eager to see.