Hypoglycemia has to be one of the most common conditions that we treat in the newborn admitted to NICU. For many infants the transitional phase of hypoglycemia can be longer than a couple low blood sugars and as nurses commonly express, it doesn’t take long before the heels of these infants begin to resemble hamburger. For those of you who have used diazoxide in the treatment of hypoglycemia you know that it works and it works quickly to raise the blood sugar. It works by blocking the production of insulin from the pancreas, so particularly in the setting of an infant with detectable insulin levels while hypoglycemic (should be undetectable with a low blood sugar) it can be quite effective. In my own practice I have found that often within one or two doses of the medication with treatment being 5-15 mg/kg/d it can seem to work miracles. Years ago I heard rumours of a trial from birth of this medication in infants of diabetic mothers but saw nothing come to fruition. As someone though who really strives to critically look at every needle poke and strongly consider the need I have always leaned towards the use of this medication if only to reduce what I suspected would be a large number of heel lances.

A Study Comes Forward

Balachandran B et al published a paper on this topic this week in Acta Paediatrica entitled Randomised controlled trial of diazoxide for small for gestational age neonates with hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia provided early hypoglycaemic control without adverse effects. To be clear this is a very small study with only 30 patients in total (15 in the diazoxide and 15 in the placebo arms) and as they had nothing to go on for determining a sample size needed there was no power calculation. The authors chose to look at a very specific group of neonates that were SGA and had hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia so we need to resist extrapolating to other patient groups such as IDMs in case there is a positive effect here.

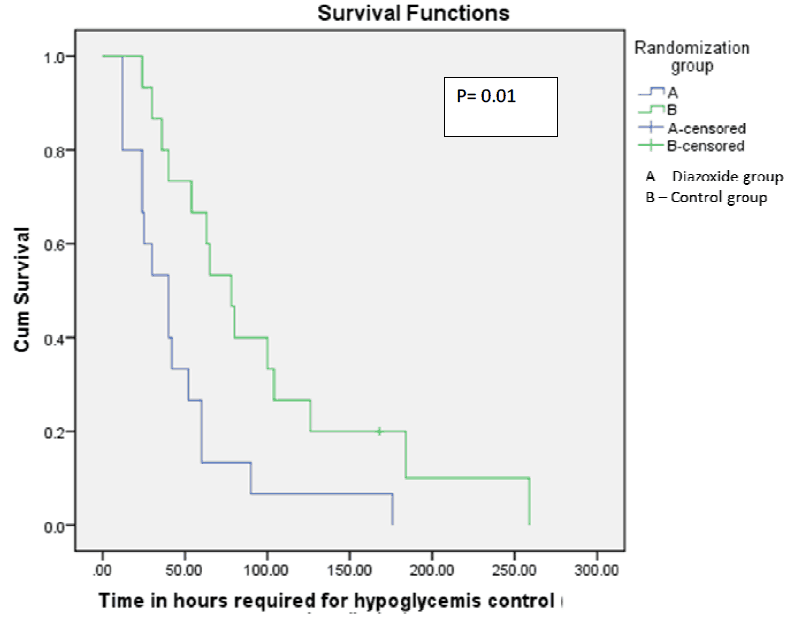

With those warnings though, what they did was devise a stepwise approach to initiating diazoxide at 8 mg/kg/d and escalating the dose to as much as 12 mg/kg/d followed by a standardized wean following blood glucose stability. The primary outcome in this case was the number of hours required to achieve a stable glucose with a glucose infusion rate of =< 4mg/kg/min. They examined a number of secondary outcomes as well including duration of IV fluids, episodes of sepsis and time to achieve full feeds as well as mortality. Given the small sample size though I would resist drawing too many conclusions about these secondary outcomes but they are reported nonetheless.  From the paper the Kaplan Meier curve indicates a faster time to stability of blood sugars for 6 hours favouring the diazoxide group. Importantly there were no differences in baseline insulin or cortisol levels between the groups which might explain differing times to glycemic control. Intravenous reductions with feeding increments were also standardized for the study to ensure comparable treatment strategies aside from the provided diazoxide or placebo.

From the paper the Kaplan Meier curve indicates a faster time to stability of blood sugars for 6 hours favouring the diazoxide group. Importantly there were no differences in baseline insulin or cortisol levels between the groups which might explain differing times to glycemic control. Intravenous reductions with feeding increments were also standardized for the study to ensure comparable treatment strategies aside from the provided diazoxide or placebo.

Claim of Safety

The authors note there were no differences in mortality or number of sepsis episodes between the groups. They did find a statistically significant reduction in duration of IV fluid requirements which is likely believable despite my earlier warning as the length of time to achieve control was significantly reduced. The fact remains though with such few patients I would take claims of safety with a grain of salt. You might think at this point though that I would be a champion for the therapy but despite my earlier enthusiasm I do have some reservations. The median time to achieve glycemic control was 40 vs 72.5 hours with a p value of 0.015 which is certainly significant but really we are talking about nearly 2 vs 3 days of management. Is diazoxide truly safe enough to warrant the 30 hour reduction in time to glycemic control? Assuming q3h point of care glucose checks this would be about 8-10 less pokes as a best case scenario but more likely 4-6 less as near the end of checking glucoses as the patient becomes more stable the number of pokes usually decreases. Is diazoxide worth it though?

Back in 2015 the FDA issued a warning that diazoxide can lead to pulmonary hypertension. In truth we have seen it in babies where I practice and as such now routinely have an ECHO done before starting the drug to determine if there is any pulmonary hypertension prior to starting the drug and if there is even a hint it is contraindicated. It isn’t too common a complication as in the FDA bulletin (read here) there have been only 11 cases reported since 1973 but it is a risk nonetheless.

Thirty patients sadly isn’t enough to rule out this complication and it is worth nothing that the authors did not look for this outcome so we don’t know if any patients suffered this.

Am I saying that one should never use diazoxide? Absolutely not but I am suggesting that if you use it then use it with great caution. Although I am delighted the authors chose to perform this study taking all risks into account and looking at the benefit in terms of time on IV and that needed to gain control of blood sugars I can’t say this should be standard of care.

Thanks for your review!

Were you aware of a kind of similar trial (in Canada!), not published yet:

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT00994149

This trial started diazoxide even earlier in unsymptomatic hypoglycemia in order te prevent the need for iv glucose.

Trial was already finished in 2011 according to the study protocol. Therefore I contacted the corresponding author 1.5y ago: Trial had indeed already been finished, but they were still analyzing

Chris I had heard of this trial but had not realized it was done