The modern NICU is one that is full of patients on CPAP these days. As I have mentioned before, the opportunity to intubate is therefore becoming more and more rare is non-invasive pressure support becomes the mainstay of therapy. Even for those with established skills in placing an endotracheal tube, the number of times one gets to do this per year is certainly becoming fewer and fewer. Coming to the rescue is the promise of easier intubations by being able to visualize an airway on a screen using a video laryngoscope. The advantage to the user is that anyone who is watching can give you some great tips and armed with this knowledge you may be better able to determine how to adjust your approach.

For those of you who have followed the blog for some time, you will recall this is not the first time video laryngoscopy has come up. I have spoken about this before in Can Video Laryngoscopy Improve Trainee Success in Intubation. In that piece, the case was made that training residents how to intubate using a video laryngoscope (VL) improves their success rate. An additional question that one might ask though has to do with the quality of the intubation. What if you can place a tube using a video laryngoscope but the patient suffers in some way from having that piece of equipment in the mouth? Lucky for us some researchers from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia have completed a study that can help answer this additional question.

Video Laryngoscopy may work but does it cause more harm than good?

Using a video laryngoscope requires purchasing one first and they aren’t necessarily cheap. If they were to provide a better patient experience though the added cost might well be worth it. Pouppirt NR et al published Association Between Video Laryngoscopy and Adverse Tracheal Intubation-Associated Events in the Neonatal Care Unit. This study was a retrospective comparison of two groups; one having an intubation performed with a VL (n=161 or 20% of the group) and the other with a standard laryngoscope (644 or 80% of the group). The study relied on the use of the National Emergency Airway Registry for Neonates (NEAR4NEOs), which records all intubations from a number of centres using an online database and allows for analysis of many different aspects of intubations in neonates. In this case the data utilized though was from their centre only to minimize variation in premedication and practitioner experience.

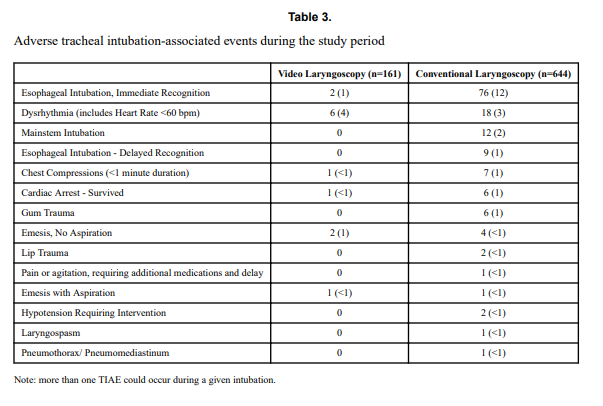

Tracheal intubation adverse events (TIAEs) were subdivided into severe (cardiac arrest, esophageal intubation with delayed recognition, emesis with witnessed aspiration, hypotension requiring intervention (fluid and/or vasopressors), laryngospasm, malignant hyperthermia, pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum, or direct airway injury) vs non-severe (mainstem bronchial intubation, esophageal intubation with immediate recognition, emesis without aspiration, hypertension requiring therapy, epistaxis, lip trauma, gum or oral trauma, dysrhythmia, and pain and/or agitation requiring additional medication and causing a delay in intubation.

Looking at the patient characteristics and outcomes, some interesting findings emerge.

Patients who had the use of the VL were older and weighed more. They were more likely to have the VL used for airway obstruction than respiratory failure and importantly were also more likely to receive sedation/analgesia and paralysis. These researchers have also recently shown that the use of paralysis is associated with less TIAEs so one needs to bear this in mind when looking at the rates of TIAEs. There were a statistically significant difference in TIAEs of any type of 6% in the VL group to 19% in the traditional laryngoscopy arm but severe TIAEs showed not difference.

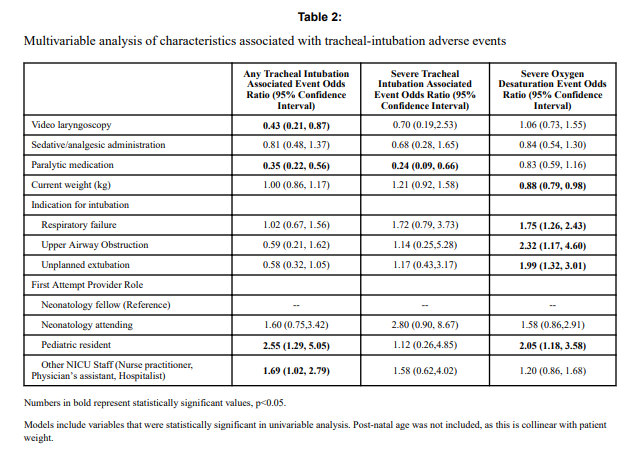

Given that several of the baseline characteristics might play a role in explaining why VL seemed superior in terms of minimizing risk of TIAEs by two thirds, the authors performed a multivariable analysis in which they took all factors that were different into account and then looked to see if there was still an effect of the VL despite these seemingly important differences. Interestingly, use of VL showed an Odds ratio of 0.43 (0.21,0.87 95% CI) in spite of these differences.

What does it mean?

Video laryngoscopy appears to make a difference to reducing the risk on TIAEs as an independent factor. The most common TIAE was esophageal intubation at 10% and reducing that is a good thing as it leads to fewer intubation attempts. This was also sen as the first attempt success was 63% in the VL group vs 44% in the other.

Now we need to acknowledge that this was not a randomized controlled trial so it could indeed be that there are other factors that the authors have not identified that led to improvements in TIAEs as well. What makes this study so robust though is the rigour with which the centre documents all of their intubations using such a detailed registry. By using one centre much of the variability in practice between units is eliminated so perhaps these results can be trusted. Would your centre achieve these same results? Maybe not but it would certainly be interesting to test drive one of these for a period of time see how it performs.

I’m all for VL – we purchased a setup not that long ago. Issue is that in anything less than a level 3 NICU, the vast majority of intimations occur in the case room where VL is not likely to be available. The few times I could have used VL, I thought it was better to practice conventionally.

We were just talking about this today. The caseroom is a tough place to use it due to the short period of time you have to really set up. I think though with time we will find this becoming much more commonplace