In recent years we have moved away from measuring and reporting gastric residuals. Checking volumes and making decisions about whether to continue feeding or not just hasn’t been shown to make any difference to care. If anything it prolongs time to full feeds without any demonstrable benefits in reduction of NEC. This was shown in the last few years by Riskin et al in their paper The Impact of Routine Evaluation of Gastric Residual Volumes on the Time to Achieve Full Enteral Feeding in Preterm Infants. Nonetheless, I doubt there is a unit in the world that has not had the following situation happen. It is 2 AM and the fellow on call is notified that they need to come and see a patient. On arrival the bedside nurse shows them a syringe that contains dark green murky fluid. The fellow is told that NG tube placement was just being checked and this is what was aspirated. The infant is fine in terms of exam but the question is asked “What should I do with this fluid”. The decision is made that the fluid looks “gross” and they discard it and then decide to resume feedings with a fresh batch of milk. Both parties feel good about discarding what looked totally unappealing for anyone to ingest and the night goes on. If this sounds familiar it should as I suspect this happens frequently.

Logical Fallacy

A colleague of mine introduced me to this concept and I think it may apply here. Purdue University’s writing lab defines a Logical Fallacy in this way “Fallacies are common errors in reasoning that will undermine the logic of your argument. Fallacies can be either illegitimate arguments or irrelevant points, and are often identified because they lack evidence that supports their claim.”

I think we may have one here that has pervaded Neonatology across the globe. Imbedded in the fallacy is the notion that because the dark green aspirates look gross and we often see such coloured aspirates in patients with necrotizing enterocolitis or other bowel disease, all green aspirates must be bad for you. The second fallacy is that the darker the aspirate the more seriously you should consider discarding it. This may surprise you but on their own there isn’t much of anything that has been shown to be wrong with them. Looking for evidence to demonstrate increased rates of NEC or other abdominal issues in an otherwise well patient finds pretty much nothing to support discarding.

A challenge to discarding

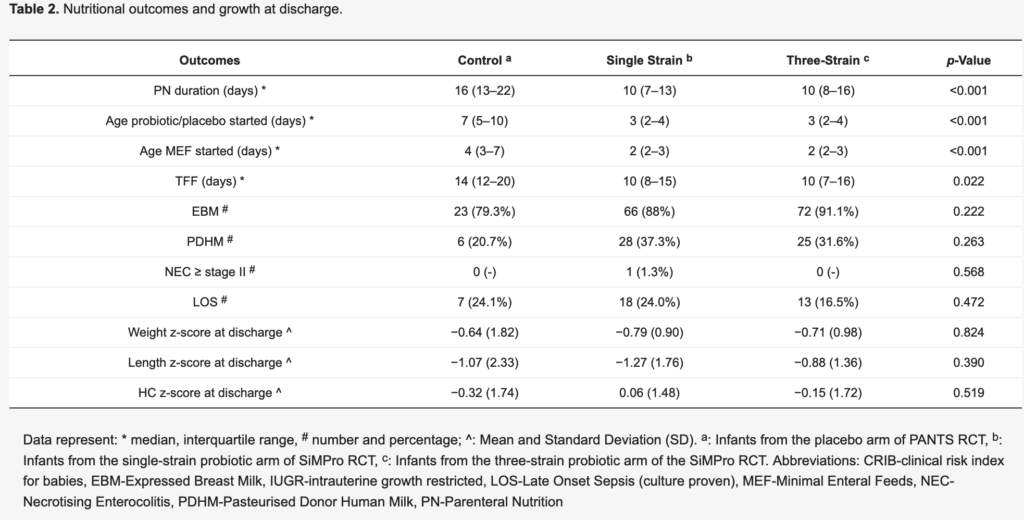

Athalye-Jape G et al published Composition of Coloured Gastric Residuals in Extremely Preterm Infants-A Nested Prospective Observational Study. The study was a nested one in that questions about gastric residuals were taken from two studies on the use of probiotics. As with other studies on the use of probiotics there were some benefits seen as shown in Table 2 but that is not the main reason for sharing this study with you.

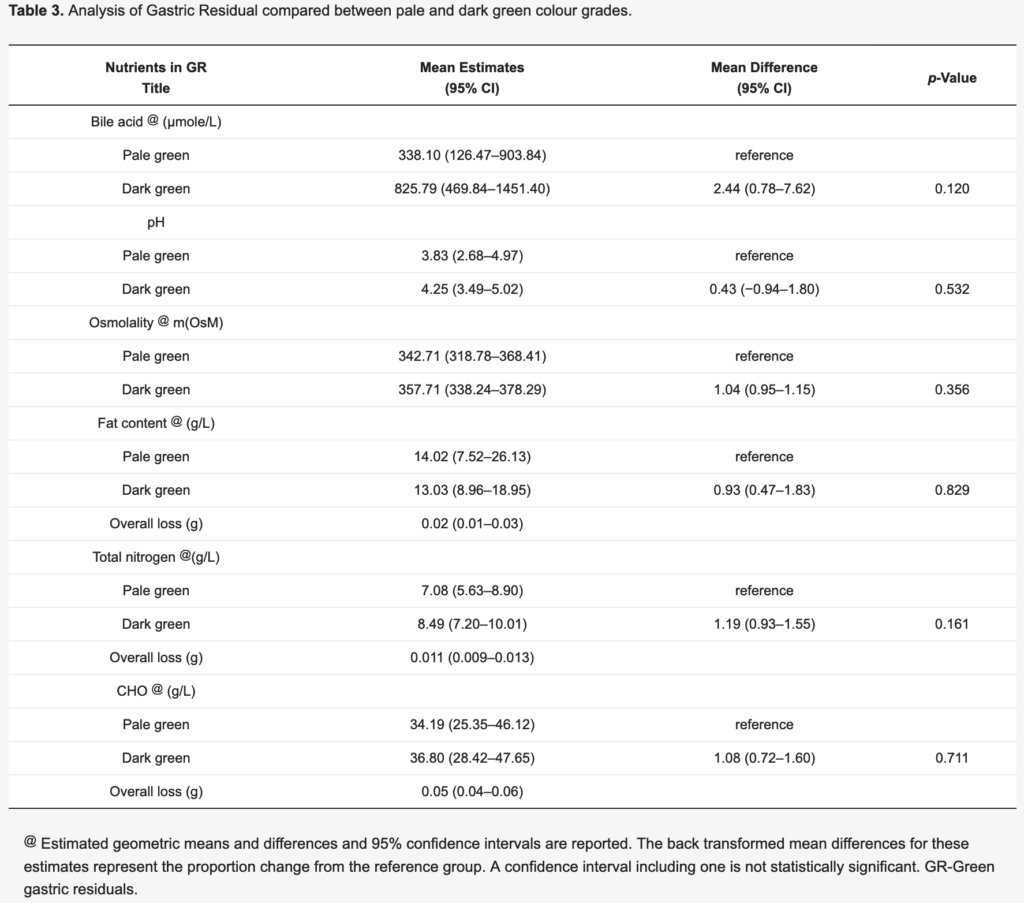

The main reason for the share of this paper is what is in Table 3.

Although not significantly different the mean estimates for concentration of bile acids in the pale and dark green aspirates came close to being different. Other nutritional content such as fat, protein and carbohydrate were no different. As the bile became darker though the bile acids tended to increase. It is this point that is worthy of discussion.

A Breakdown of the Aspirate

I’m with you. When you look at that murky dark green fluid in the syringe it just seems wrong to put that back into a belly. Would you want to eat that? Absolutely not but when you break it down into what is in there, suddenly it doesn’t seem so bad. We assume that we would not want to refeed such putrid looking material and that is where the logical fallacy exists. What evidence do we have that refeeding that fluid is bad? As I said above not much at all. Looking at the fact that there is actual nutritional calories in that fluid and bile acids as well you come to realize that throwing it away may truly not be in the best interest of the baby. Calories may wind up in the garbage and along with them, bile acids.

Bile acids are quite important in digestion as they help us digest fat and moreover as they enter the ileum they are reabsorbed in large quantities which go to further help digestion. In addition bile acid concentrations are what helps draw fluid into bile and promotes bile flow. By throwing these bile acids out we could see lower bile volumes and possible malabsorption from insufficient emulsification of fat.

The other unmeasured factors in this fluid are the local hormones produced in the bowel such as motilin which helps with small bowel contractility. Loss of this hormone might lead to impairment of peristalsis which can lead to other problems such as bacterial overgrowth and malabsorption.

Now all of this is speculative I will admit and to throw out one dark green aspirate is not going to lead to much harm I would think. What if this was systematic though over 24 or 48 hours that such aspirates were being found and discarded. Might be something there, What I do think the finding of such aspirates should trigger however is a thorough examination of the patient as dark green aspirates can be found in serious conditions such as NEC or bowel perforation. In the presence of a normal examination with or without laboratory investigations what I take from this study is that we should question are tendency to find and discard. Maybe the time has come to replace such fear with a practice of closing our eyes and putting that dark green aspirate right back where it came from.

Insightful and we need to find out more to answer this question. Please see our work here http://www.grvstudy.com/