by All Things Neonatal | May 19, 2016 | resuscitation, Uncategorized

As I was preparing to settle in tonight I received a question from a reader on my Linkedin page in regards to the use of sustained inflation (SI) in our units. We don’t use it and I think the reasons behind it might be of interest to others. The concept of SI is that by providing a high opening pressure of 20 – 30 cm H2O for anywhere from 5 to 15 seconds one may be able to open the “stiff” lung of a preterm infant with RDS and establish an adequate functional residual capacity. Once the lung is open, it may be possible in theory to keep it open with ongoing peep at a more traditional level of 5 – 8 cm of H20.

The concept was tested 25 years ago by Vyas et al in their article Physiologic responses to prolonged and slow-rise inflation in the resuscitation of the asphyxiated newborn infant. In this study, 9 newborn infants were given a relatively short 5 second sustained inflation and led to earlier and larger lung volumes with good establishment of FRC. Like many trials in Neonatology though sceptics abound and here we are 25 years later still discussing the merits of this approach.

As I have a warm place in my heart for the place that started my professional career whenever I come across a paper published by former colleagues I take a closer look. Such is the case with a systematic review on sustained inflation by Schmolzer et al. The inclusion criteria were studies of infants born at <33 weeks. Their article provides a wonderful assessment of the state of the literature on the topic and I would encourage you to have a look at it if you would like a good reference to keep around on the topic. What it comes down to though is that there are really only four randomized human studies using the technique and in truth they are fairly heterogeneous in their design. They vary in the length of time an SI was performed (5 – 20 seconds), the pressures used (20 – 30 cm H2O), single or multiple SIs and lastly amount of oxygen utilized being 21 – 100%. In fact three of the four studies used either 100% or in one case 50% FiO2 when providing such treatments.

What Did They Show?

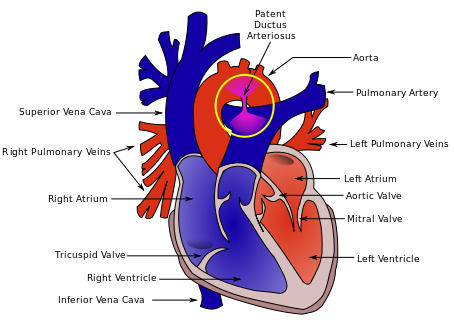

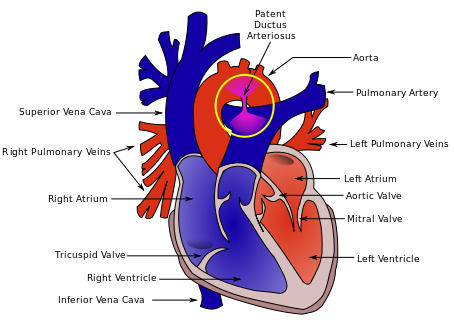

This is where things get interesting. SI works in the short term by reducing the likelihood that an infant will need mechanical ventilation at 72 hours with a number needed to treat of only 10! In medicine we normally would embrace such results but sadly the results do not translate into long term benefits as the rate of BPD, mortality and the combined outcome do not remain significant. Interestingly, the incidence of a symptomatic PDA needing treatment with either a medical or surgical approach had a number needed to harm of 11; an equally impressive number but one that gives reason for concern.  As the authors speculate, the increased rate of PDA may be in fact related to the good job that the SI does in this early phase. By establishing an open lung and at an earlier time point it may well be that there is an accentuation in the relaxation of the pulmonary vasculature and this leads to a left to right shunt that by being hemodynamically significant helps to stent the ductus open at a time when it might otherwise be tending to close. This outcome in and of itself raises concern in my mind and is the first reason to give me reason to pause before adopting this practice.

As the authors speculate, the increased rate of PDA may be in fact related to the good job that the SI does in this early phase. By establishing an open lung and at an earlier time point it may well be that there is an accentuation in the relaxation of the pulmonary vasculature and this leads to a left to right shunt that by being hemodynamically significant helps to stent the ductus open at a time when it might otherwise be tending to close. This outcome in and of itself raises concern in my mind and is the first reason to give me reason to pause before adopting this practice.

Any other concerns?

Although non-significant there was a trend towards increased rates of IVH in the groups randomized to SI. There is real biologic plausibility here. During an SI the increased positive pressure in the chest could well simulate a similar effect to a pneumothorax and impede the passive drainage of blood from the head into the thorax. In particular, longer durations and/or frequent SIs could increase such risk. Given the heterogeneous nature of these studies it is difficult to know if they all had been similar in providing multiple SIs could we have seen this cross over to significant?

I believe the biggest concern in all of this though is that I would have a very hard time applying the results of these studies to our patient population. The systematic review addresses the question about whether SI is better than IPPV as a lung recruitment strategy in the preterm infant with respiratory distress. I have to say though we have moved beyond IPPV as an initial strategy in favour of placement of CPAP on the infant directly after birth. The real question in my mind is whether providing brief periods of SI followed by CPAP of +6 to +8 is better than placement on CPAP alone as a first strategy to establish good lung volumes.

If I am to be swayed by the use of SI someone needs to do this study first. The possibility of increasing the number of hemodynamically significant PDAs and potentially worsening IVH without any clear reduction in BPD is definitely placing me firmly in the camp of favouring the CPAP approach. Having said all that, the work by the Edmonton group is important and gives everyone a glimpse into what the current landscape is for research in this field and opens the door for their group or another to answer my questions and any others that may emerge as this strategy will no doubt be discussed for years to come.

by All Things Neonatal | May 11, 2016 | drug withdrawal, NAS, Uncategorized

Original Post

I don’t know if you missed it but I did until tonight. We don’t have this in Canada but there have been some US states that have been doing so for the past while. You may find the following link very interesting that explains the positions of each state in regards to drug use in pregnancy. The intentions were good to protect the unborn child but the consequences to mother’s who tested positive were of great concern. While testing of mothers for drug use has been done off and on for years what made this different was that the confirmation of drug use was deemed to be a criminal offense with the results handed over to the police.

As this article from March 4th indicates the practice has been ongoing in Tennessee for at least a year and a pilot project was planned for Indiana this year. According to the article the situation in Tennessee came with some significant risk to the mother if found to have a positive screen.

“Lawmakers in Tennessee last year increased drug screenings of expectant mothers and passed a law allowing prosecutors to charge a woman with aggravated assault against her unborn baby if she was caught using illicit drugs. The penalty is up to 15 years in prison.”

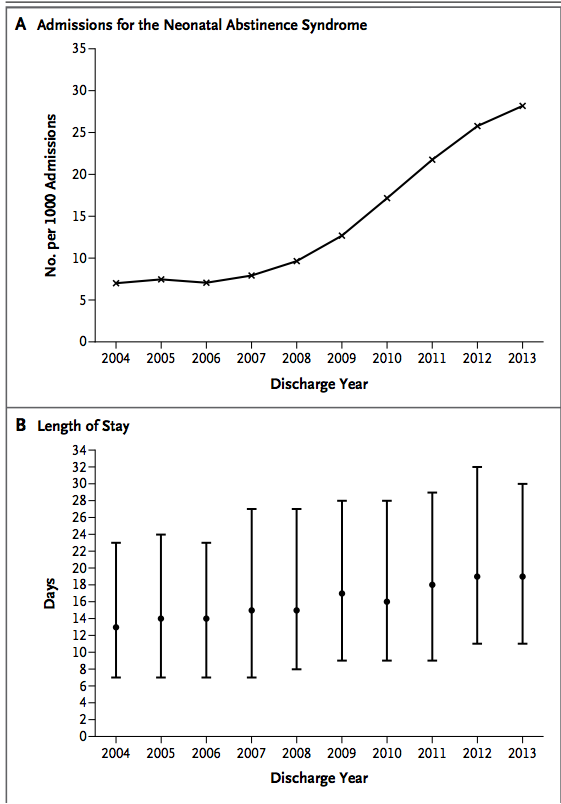

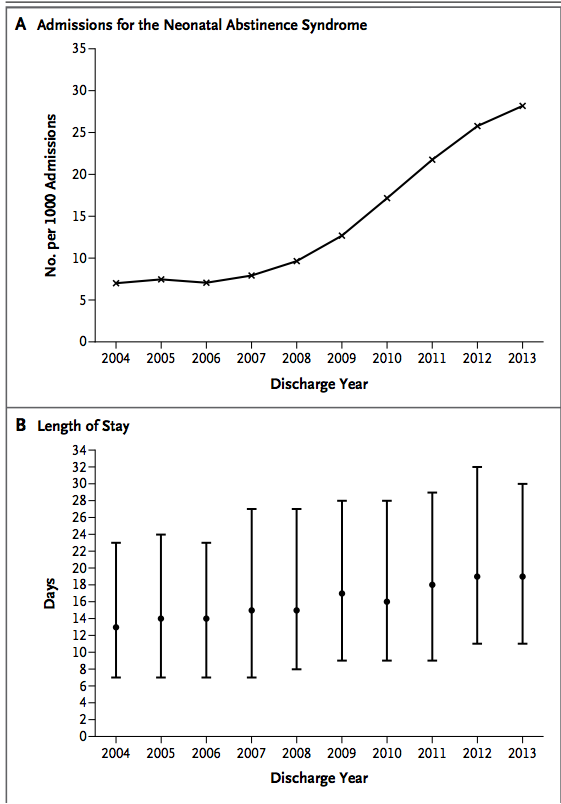

The law may seem harsh and in my eyes is but it came in response to the tidal wave of drug addiction and neonatal withdrawal in the US as was identified in the article from the NEJM in 2015 entitled Increasing Incidence of the Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome in U.S. Neonatal ICUs. The impact on neonatal ICUs in the US can be seen in the following graphs which demonstrate not only the phenomenal rise in the incidence of the problem but in the second graph the gradually prolonging length of stay that these patients face.  Aside from the societal issues these families face and the problems their infants experience, the swelling volume of patients NICUs have to contend with are quite simply overwhelming resources with time. Although I reside in Canada, it is the trend shown that likely motivated some states to adopt such a draconian approach to these mother-infant dyads.

Aside from the societal issues these families face and the problems their infants experience, the swelling volume of patients NICUs have to contend with are quite simply overwhelming resources with time. Although I reside in Canada, it is the trend shown that likely motivated some states to adopt such a draconian approach to these mother-infant dyads.

There are so many questions that would arise from such an approach.

- What if a mother refuses testing as is the option in Indiana. Would Child and Family services be called simply on the suspicion?

- What if a mother received prescription opioids for chronic back pain or used an old prescription in the days before she was tested after a fall to ease her pain?

- Then there is the Sharapova situation

where a mother could conceivably take a medication that she is unaware is on a list of “banned substances”. What about Naturopathic or herbal supplements that might test positive?

where a mother could conceivably take a medication that she is unaware is on a list of “banned substances”. What about Naturopathic or herbal supplements that might test positive?

- Then what about false positive tests?

The ramifications of any of the above situations on the family unit could be devastating. Interestingly this year the courts in Indiana passed a law that prevents health care providers from releasing the results of such toxicology screens to police without a court order so indeed there would need to be suspicion. In the end though is it right?

Tennessee Sings a New Tune

As surprised as I was to hear about the situation in Tennessee just now I was equally surprised to come across a U.S. Supreme Court ruling handed down March 21st, 2001 that has ruled that subjecting mothers to such testing in hospitals is unconstitutional. This may disclose my ignorance of US law but I would have thought if the US Supreme Court says you cannot do something the states would follow along but at least in Tennessee that was not the case…until now.

March 23rd the law in Tennessee is changing as the state has chosen not to renew the legislation after a two year trial period saw about 100 women arrested. For more information on this decision see Assault Charges for Pregnant Drug Users Set to Stop in Tennessee.

Where do we possibly go from here?

I found this whole storyline shocking but I am taking some solace in knowing that this was a very limited experiment in one state. Neonatal abstinence is a problem and a big one at that. Criminalizing mothers though is not an effective solution and to me the solution to this problem will need to involve a preventative approach rather than one of punishment. A first step in the right direction will be to stem the tide of liberal use of prescription opioids in pregnancy as was suggested in the BMJ news release in January of this year. In the end if we as medical practitioners are freely prescribing such medications to the mothers we care for perhaps we should look in the mirror when pointing fingers to determine fault. So many of the mothers and the infants we care for may well be victims of a medical establishment that has not done enough to prevent the problem.

Update

While screening women presenting to the hospital in labour or their newborns for that matter may seem like a wise choice, the request to procure a sample remains just that. It is a request and in collecting consent is needed. This was the advice at least I was given by the Canadian Medical Protective Association. It does create an interesting situation though in the mother who refuses to have her or her baby submit a urine specimen. Should we assume that a woman who refuses testing is in fact using an illicit substance or is she merely choosing to not have a wasted test when she knows that she is not using anything? How do we as practitioners view this decision and do we jump to a verdict of guilt immediately? I suspect the answer is that most of us would assume so especially if we are using a targeted screening approach in which we are only approaching those mothers who we suspect are using.

The secondary question becomes the “so what”? What I mean by this is how will our management change if we know or don’t know? If we suspect use and the baby is demonstrating signs of withdrawal abstinence scoring will start. If the source of the symptoms are unknown would we not just treat with phenobarbital to cover the possibility that there is more than one drug at play here? I used to be on the side of the argument that felt we had to know and therefore pushed for such screening but in the end will it really change our management? Not really.

This past month the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) issued a committee opinion on opioid use in pregnancy. The important points to share with you are the following and I would agree with each.

- Screening for substance use should be part of comprehensive obstetric care and should be done at the first prenatal visit in partnership with the pregnant woman. Screening based only on factors, such as poor adherence to prenatal care or prior adverse pregnancy outcome, can lead to missed cases, and may add to stereotyping and stigma. Therefore, it is essential that screening be universal

- Urine drug testing has also been used to detect or confirm suspected substance use, but should be performed only with the patient’s consent and in compliance with state laws.

- Breastfeeding should be encouraged in women who are stable on their opioid agonists, who are not using illicit drugs, and who have no other contraindications, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Women should be counseled about the need to suspend breastfeeding in the event of a relapse.

The issue of consent seems to be firmly in place based on this position and as I mention above I think that is a good thing. The question of breastfeeding comes up frequently and it is good to see ACOG take a clear view on this as I have often thought that the benefits of the same plus the administration of small quantities of the drug in the milk may have a double benefit in reducing symptoms.

.

by All Things Neonatal | May 4, 2016 | congenital heart defects, Uncategorized

As evidence mounts for the use of pulse-ox screening to detect congenital heart defects a few key points have arisen. The evidence comes from many publications but one of the best which summarizes the body of evidence is the systematic review by Thangaratinam S which included over 200000 asymptomatic newborns. The key here is to note that as this is a screening test if there are symptoms of congenital heart disease one should be referring to a specialist to rule out a significant CHD rather than spending time with such screening tests. The four points to highlight though are:

- Comparing preductal to postductal saturations enhances sensitivity

- Performing such testing after 24 hours decreases false positive results from conditions leading to desaturation that are not CHD such as TTN.

- The false positive rate is 0.14% if the first two criteria are applied using the cutoffs of < 95% in any limb or > 3% difference between pre and post ductal locations.

- Pulse-ox screening does not detect ALL CHD but rather the ones that are deemed critical or immediately life threatening if not identified in the newborn period.

| Examples of CCHD Lesions Detectable with Pulse Oximetry Screening |

| Most consistently cyanotic |

May be cyanotic |

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS)

Pulmonary atresia with intact septum (PA IVS)

Total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR)

Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF)

Transposition of the great arteries (TGA)

Tricuspid atresia

Truncus arteriosus |

Coarctation of the aorta (COA)

Double outlet right ventricle (DORV)

Ebstein anomaly

Interrupted aortic arch (IAA)

Single ventricles

|

Is there a danger in screening too early?

As you screen closer to birth the risk of detecting conditions leading to desaturation which are not CHD rises. Common conditions such as TTN or mild pulmonary hypertension may mimic CHD and lead to a false positive finding. Thinking of the hospital environment, how many patients are sent to triage beds on a daily basis with tachypnea and mild desaturation?

This month the first real assessment of screening in the home environment was completed by Cawsey MJ entitled Feasibility of pulse oximetry screening for critical congenital heart defects in homebirths. This study describes in a retrospective fashion the results of applying a pulse-ox screening protocol in the UK to 90 babies screened at 2 hours of age. This study is important as the typical early discharge of patients from birth centres or could potentially benefit as well by having the results of such work available. Out of the 90 patients screened 4 had abnormal results and after rescreening two were normal but 2 were persistently abnormal and required admission for further workup. Neither of the two had CHD but were diagnosed with congenital pneumonia.

This yields a false positive rate of 2% or about 16 times as high as screening after 24 hours.

How do we apply the results?

As the saying goes “something is better than nothing”. In the home or birthing centre environment, waiting until after 24 hours to perform the screen may not be possible either due to the midwife leaving after the delivery or in the case of a birth centre the couple leaving before 6 hours as is the case in our local centre. As I see it all is not lost in doing screening in such circumstances early as one may detect TTN, pneumonia or another vascular condition such as PPHN before it becomes symptomatic. Intervening earlier in the course of the illness may actually result in better outcomes for the infant. We have to be careful though when looking at the ability of this screen to detect CHD. The truth is there are not enough patients screened in this study to really draw any conclusions. With an incidence of about 1:100 births a sample of 90 patients would be lucky to find one patient so the absence of any detected patients is not surprising.

The study though does draw attention to a couple important points. First as mentioned above, the midwife has the opportunity by screening early to detect ANY cause of desaturation and then plan for further management. Secondly, it does raise the question with a 2% false positive rate whether screening programs regardless of home or birth centre should include follow-up by a midwife after 24 hours to do testing. My vote would be a resounding yes. If applied to a population there would certainly be kids detected with CHD over time and reducing the false positive rate is important in terms of the downstream consequences of overwhelming our Cardiology colleagues who would ultimately need to see such patients to rule in or out significant CHD.

I am not a midwife, nor do I attend home or birthing centre deliveries but I would ask that the consideration of such screening programs consider the timing of testing as sending 2 per 100 deliveries vs 1 in 1000 deliveries for further assessment to rule out CHD is something that our overwhelmed health care systems need to consider strongly.

by All Things Neonatal | Apr 27, 2016 | Infection, reflux, Uncategorized

Preamble

May 7, 2017

As I sit drinking my morning coffee and feeling a little sense of heartburn I began to reflect on the fact that I can’t recall the last time I prescribed ranitidine or a PPI in an infant for anything other than an acute upper GI bleed. I know I had done so after moving to Winnipeg in 2010 at a few time points but that practice has certainly died at least for me. You know what? I don’t think it has made one iota of difference but based on the results from this post I think it is for the best. What has inspired my republishing of this post is my question as to whether or not you think your units practice has changed as well since the revelation that these medications are not only ineffective but harmful. Read on and enjoy your Sunday

Choosing wisely is an initiative to “identify tests or procedures commonly used whose necessity should be questioned and discussed with patients. The goal of the campaign is to reduce waste in the health care system and avoid risks associated with unnecessary treatment.”

The AAP Section on Perinatal Pediatrics puts the following forth as one of their recommendations.

“Avoid routine use of anti-reflux medications for treatment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or for treatment of apnea and desaturation in preterm infants.

Gastroesophageal reflux is normal in infants. There is minimal evidence that reflux causes apnea and desaturation. Similarly, there is little scientific support for the use of H2 antagonists, proton-pump inhibitors, and motility agents for the treatment of symptomatic reflux. Importantly, several studies show that their use may have adverse physiologic effects as well as an association with necrotizing enterocolitis, infection and, possibly, intraventricular hemorrhage and mortality.”

How strong is the evidence?

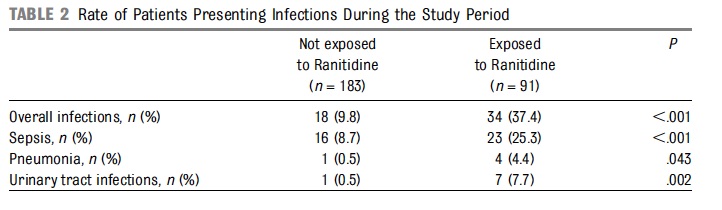

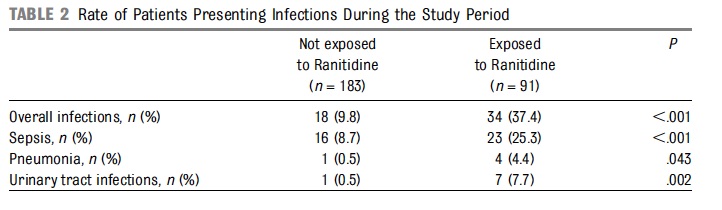

The evidence for risk with acid suppression is largely based on either retrospective or in the case of Terrin G et al a prospective observational cohort study Ranitidine is Associated With Infections, Necrotizing Enterocolitis, and Fatal Outcome in Newborns. In this study the authors compared a group of premature infants with birth weights between 401 – 1500g or 24 – 32 weeks gestation who received ranitidine for reflux symptoms to those who did not. All told 91 were exposed while 183 were not. The authors are to be commended for standardizing the feeding protocol in the study so that when comparing NEC between groups one could not blame differences in formula consumption or rate of feeding advancement. Additionally, bias was controlled by having those not involved in care collect outcome data without knowing the purpose of the study. Having said that, they may have been able to ascertain that ranitidine was used and have been influenced in their assessments.

The patients in terms of risk factors for poor outcome including CRIB and apgar scores, PDA etc were no different to explain an increased risk for adverse outcome.

From the above table, rates of infections were clearly higher in the ranitidine group but more concerning was the higher rate of mortality at 9.9% vs 1.6% P=0.003 and longer hospitalization median 52 vs 36 days P=0.001.

Results of a Meta-Analysis

Additional, evidence suggesting harm comes from a meta-analysis on the topic by More K, Association of Inhibitors of Gastric Acid Secretion and Higher Incidence of Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Preterm Very Low-Birth-Weight Infants. This analysis actually includes the study by Terrin and only one other retrospective database study of 11072 patients by Guillet et al. As the reviewers point out the study by Terrin while prospective did not employ the use of multiple regression to adjust for confounders while the larger study here did. In the end the risk of NEC with the use of acid suppression was 1.78 (1.4 – 2.27; p<0.00001).

What do we do with such evidence?

I can say this much. Although small in number, the studies that are available will make it very difficult to ever have a gold standard RCT done on this topic. This scant amount of evidence, backed by the biologic plausibility that raising the gastric pH will lead to bacterial overgrowth and potential aspiration of such contents provides the support for the Choosing Wisely position.

Why do we continue to see use of such medications though? It is human nature I suspect that is the strongest motivator. We care for infants and want to do our best to help them through their journey in neonatal units. When we hear on rounds that the baby is “refluxing” which may be documented by gulping during a brady, visible spit ups during A&Bs or through auscultation hearing the contents in the pharynx we feel the need to do something. The question invariably will be asked whether at the bedside or by the parents “Isn’t there something we can do?”.

My answer to this is yes. Wait for it to resolve on its own, especially when the premature infants are nowhere close to term. I am not sure that there is any strong evidence to suggest treatment of reflux episodes with gastric acid suppression helps any outcomes at all and as we see from the Terrin study length of stay may be prolonged. I am all in favour of positional changes to reduce such events but with respect to medications I would suggest we all sit on our hands and avoid writing the order for acid suppression. Failure to do so will likely result in our hands being very busy for some infants as we write orders to manage NEC, pneumonia and bouts of sepsis.

by All Things Neonatal | Apr 20, 2016 | jaundice, Uncategorized

As the saying goes “What is old is new again” and that may be applicable here when talking about prevention of kernicterus. In the 1990s there was a great interest in a class of drugs called mesoporphyrins in the management of hyperbilirubinemia. The focus of treatment for many years had been elimination of bilirubin through the use of phototherapy but this shifted with the recognition that one could work on the other side of the equation. That is to prevent the production of bilirubin in the first place.

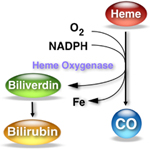

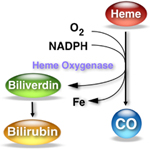

Tin mesoporphyrins (SnMP) have the characteristic of being able to inhibit the enzyme hemo oxygenase quite effectively.  By achieving such blockade the breakdown of heme to carbon monoxide and biliverdin (the precursor of bilirubin) is inhibited. In so doing, the production of bilirubin is reduced making one less dependent on phototherapy to rid the body of elevated levels. So simple and as you might imagine a good reason for there to have been significant interest in the product. One article by Martinez et al entitled Control of severe hyperbilirubinemia in full-term newborns with the inhibitor of bilirubin production Sn-mesoporphyrin. was published in 1999 and demonstrated that infants with severe hyperbilirubinemia between 48-96 hours could have their need for phototherapy eliminated by use of the product compared to 27% of the infants in the control group needing treatment. Additionally, total bilirubin samples were reduced from a median of 5 to 3 with the use of one IM injection of SnMP. This small study was hampered though by inability to really look at adverse outcomes despite its effectiveness. What has been seen however is that SnMP if given to infants who are then treated with white lights can create a rash which is not seen however when special blue light is employed.

By achieving such blockade the breakdown of heme to carbon monoxide and biliverdin (the precursor of bilirubin) is inhibited. In so doing, the production of bilirubin is reduced making one less dependent on phototherapy to rid the body of elevated levels. So simple and as you might imagine a good reason for there to have been significant interest in the product. One article by Martinez et al entitled Control of severe hyperbilirubinemia in full-term newborns with the inhibitor of bilirubin production Sn-mesoporphyrin. was published in 1999 and demonstrated that infants with severe hyperbilirubinemia between 48-96 hours could have their need for phototherapy eliminated by use of the product compared to 27% of the infants in the control group needing treatment. Additionally, total bilirubin samples were reduced from a median of 5 to 3 with the use of one IM injection of SnMP. This small study was hampered though by inability to really look at adverse outcomes despite its effectiveness. What has been seen however is that SnMP if given to infants who are then treated with white lights can create a rash which is not seen however when special blue light is employed.

Two other studies followed exploring the use of SnMP in cases of severe hyperbilirubinemia in term infants and were the subject of a Cochrane review in 2003. The conclusions of the review essentially became the death nell for the therapy as they were as follows.

“…may reduce neonatal bilirubin levels and decrease the need for phototherapy and hospitalization. There is no evidence to support or refute the possibility that treatment with a metalloporphyrin decreases the risk of neonatal kernicterus or of long-term neurodevelopmental impairment due to bilirubin encephalopathy… Routine treatment of neonatal unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia with a metalloporphyrin cannot be recommended at present.”

The literature after this basically dries up, that is until this month when a paper emerges that is best described as a story of mystery and intrigue!

Prophylactic Use of SnMP From 2003 Published in 2016!

This paper as you read it almost seems like a conspiracy story. The paper is by Bhutani et al (as in the nomogram) Clinical trial of tin mesoporphyrin to prevent neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. The study set out to answer a different question than had been previously studied. The question here was, if you provided a single IM dose of SnMP to infants who were at or above the 75%ile on the risk nomogram, could you prevent the need for phototherapy or exchange transfusion as the primary outcome. Secondarily, the authors truly wanted to demonstrate safety of the product and planned on recruiting 800 patients per arm in the study. The study appeared to be well planned and as with many studies had a safety monitoring committee which was to do interim analyses. After the first analysis the FDA became involved and recommended studies to look at a prophylactic versus therapeutic approach. Due to the interim analysis the study had been halted and after the FDA made their suggestion the study was simply never restarted as future studies were planned to look at the effectiveness and safety of the two approaches. The authors state that they planned on reporting their results in 2006/7 but elected to wait until long term data emerged. Now finally 9 years later they decided to release the results of the partially completed study. The story around this study I find as interesting as the results they obtained!

So What Happened?

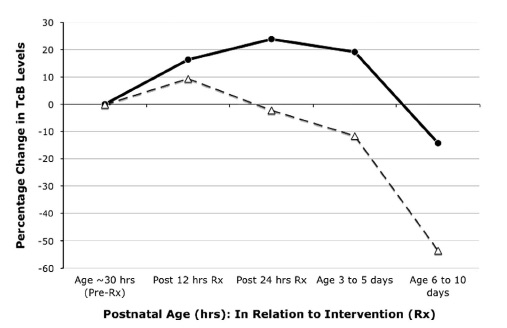

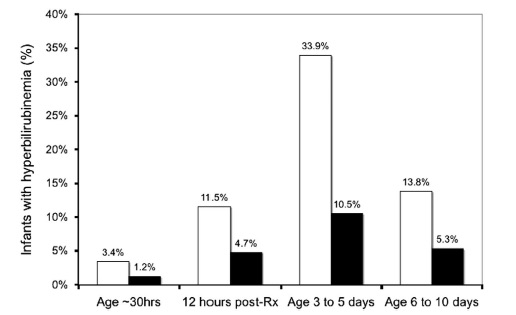

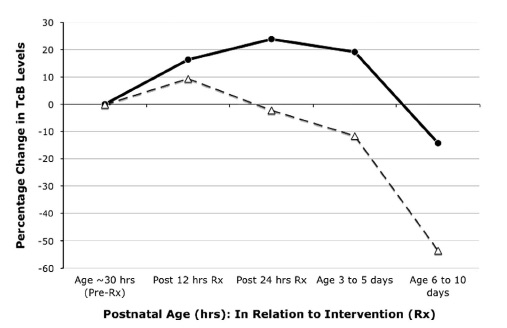

Before closing the study they managed to recruit 87 into the intervention arm and 89 into the placebo group and lost none to follow-up. One dose of SnMP had a significant effect on the trajectory of curves for bilirubin production as can be seen in the first figure.

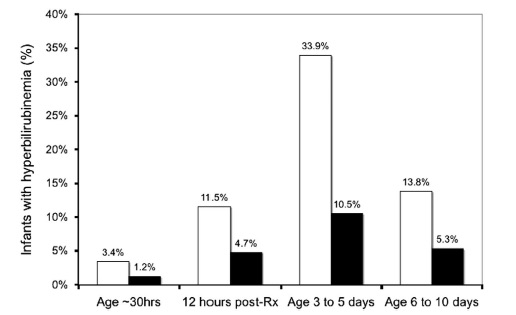

The graph below demonstrates what percentage of patients had a bilirubin level above 220 umol/L (12.9 mg/dl) after the single injection of SnMP (black bars) compared to placebo (white bars).

What can we do with these results?

It would be tough to argue anything other than this being an effective treatment to prevent significant hyperbilirubinemia. Unfortunately, like many studies that were never completed this one remains underpowered to conclusively demonstrate that the use of SnMP is safe in both the short and long term periods. The absence of such data make it very difficult to recommend SnMP as standard of care. One has to add to this that while we have evidence to show it reduces the rate of rise of bilirubin, what we don’t know is whether in a larger study the incidence of bilirubins > 425 umol/L or the need for exchange transfusion might be reduced. If this were the case, it would make for a compelling argument to try SnMP.

That is the approach for standard of care though. In the setting of a patient with a known blood group incompatibility who was at high risk for exchange transfusion, if they received IVIG and the bilirubin continued to climb might there be a role here? I would tend to say yes if we could get our hands on some. The authors by sharing this data have shown the medication is effective in doing what it is supposed to do. Given that at least in our centre all of our lights are of the new variety, the risk of rash would be nonexistent. The risk for kernicterus or at least an exchange transfusion though would not be minimal so if we have this in our toolbox I would after weighing the risks opt to give it.

I certainly wonder if there are places out there who have used it and if so what is your experience?

by All Things Neonatal | Apr 8, 2016 | preemie, Uncategorized

It seems the expression “(insert a group) lives matter” is present everywhere these days so I thought I would join in after a moving experience I had today. For those of you who have been with the blog since the beginning you would have seen a number of posts that if you follow them in time, provide a glimpse into the transformation that Winnipeg has seen over the last year or so.

Prior to that point, 24 weeks was a cutoff for resuscitation that had been in place for some time and after a great amount of deliberation and thought was changed to 23 weeks. This did not come without a great deal of angst and a tremendous amount of education and teamwork that our nurse educators and clinical leads were so instrumental in helping to role out. The experience was outlined in a couple of posts that you may find interesting if you didn’t catch them the first time. The first was Winnipeg hospital now resuscitating all infants at 22 weeks! A media led case of broken telephone. and the second being Winnipeg Hospital About to Start Resuscitating Infants at 23 weeks!

Since these two posts we have certainly had our fair share of experience as we have seen far more babies than anticipated but the region has met the challenge head on and although the numbers are small we appear to have not only more survivors than expected but all but one infant had gone home without O2 and all have been demand feeding at discharge. While we await the 18 month outcomes, the results thus far appear reassuring.

A Special & Memorable Visit

Then today, a visit occurred from the first of such infants who is now just over a year of age. He was bright eyed, smiling, interactive and by his parent’s account, has normal tone and assessments thus far by physiotherapy. His presence in the NICU put smiles on faces and at least for myself made me think of the expression “Micropreemie Lives Matter”. He was a baby that everyone predicted would not survive and then when he did, that he would be grossly developmentally impaired which he does not appear to be in the least. His presence in the unit no doubt gives everyone who doubted the merits of moving down this path reason to pause.

Before you accuse me of wearing rose coloured glasses, make no mistake I know that he will not represent the outcome for everyone. In fact at one of our hospitals two of such infants have died while we await the 18 month outcomes for the other survivors. What his presence does though, is remind us or at least me that good outcomes are possible and in the case of our experience in Winnipeg may be more common that we thought they would be.

Black Swans and Human Nature

When I have spoken to audiences about the path forward when resuscitating such ELGANS I have often commented on the “Black Swan” effect.  This was very nicely described by Nassim Taleb and described the human trait to react to unusual events with extreme reactions. An example is no one wanting to fly in the months after the world trade centre bombing when statistically this may have been the safest period in history to fly. Similarly, we as a team need to avoid the extreme reaction of saying that we should not be resuscitating such small infants when a bad outcome occurs. As I have told many people, we know these patients will not all survive, we know a significant number will have adverse development yet not all will and at least in our small sample thus far the babies would appear to be doing better overall than anticipated. If we know that bad outcomes will occur then why do we hear the questions come when they do such as “why are we doing this?”, “maybe we should rethink our position on 23 week infants”. It happens because we care and we hate seeing families and their babies go through such painful experiences. What we cannot do though for the sake of those such as our visitor today is react with a “Black Swan” reaction and steer the ship so to speak in the previous direction we were in. There are survivors and they may do well and that is why I say “Micropreemie Lives Matter”.

This was very nicely described by Nassim Taleb and described the human trait to react to unusual events with extreme reactions. An example is no one wanting to fly in the months after the world trade centre bombing when statistically this may have been the safest period in history to fly. Similarly, we as a team need to avoid the extreme reaction of saying that we should not be resuscitating such small infants when a bad outcome occurs. As I have told many people, we know these patients will not all survive, we know a significant number will have adverse development yet not all will and at least in our small sample thus far the babies would appear to be doing better overall than anticipated. If we know that bad outcomes will occur then why do we hear the questions come when they do such as “why are we doing this?”, “maybe we should rethink our position on 23 week infants”. It happens because we care and we hate seeing families and their babies go through such painful experiences. What we cannot do though for the sake of those such as our visitor today is react with a “Black Swan” reaction and steer the ship so to speak in the previous direction we were in. There are survivors and they may do well and that is why I say “Micropreemie Lives Matter”.

In the paper by Rysavy the overall finding at 23 weeks was that 1 out of 6 would survive without moderate or severe disability. What do we do as we increase our experience if the trend bears out that our outcomes are better? How will we counsel families? Will we continue to use the statistics from the paper or quote our own despite us being a medium sized centre?

The Big Questions

As our experience with such infants increases we will also no doubt see a change in our thoughts about infants at 24 weeks. I have seen this first hand already with a physician commenting today that 24 weeks is not such a big deal now! This brings me to the big question (which I will credit a nurse I work with for planting in my head in the last two weeks) which is for another time to answer as this post gets a little lengthy but is something to ponder. As our outcomes for 23 weeks improve and so do our results at 24 weeks (which is bound to happen with the more frequent team work in such situations) will our approach to infants at 24 weeks change. In our institution we generally follow the CPS guidelines for the management of infants at extremely low GA and offer the choice of resuscitation at 24 weeks. As outcomes improve at this GA will we continue to do so or will we reach a threshold where much like the case at 25 weeks we inform families that we will resuscitate their infant without providing the option of compassionate care?

It is too early to answer these questions conclusively but they are very deserving of some thought. Lastly, I would like to thank the parent who came by today for inspiring me and to all those who will follow afterwards.

As the authors speculate, the increased rate of PDA may be in fact related to the good job that the SI does in this early phase. By establishing an open lung and at an earlier time point it may well be that there is an accentuation in the relaxation of the pulmonary vasculature and this leads to a left to right shunt that by being hemodynamically significant helps to stent the ductus open at a time when it might otherwise be tending to close. This outcome in and of itself raises concern in my mind and is the first reason to give me reason to pause before adopting this practice.

As the authors speculate, the increased rate of PDA may be in fact related to the good job that the SI does in this early phase. By establishing an open lung and at an earlier time point it may well be that there is an accentuation in the relaxation of the pulmonary vasculature and this leads to a left to right shunt that by being hemodynamically significant helps to stent the ductus open at a time when it might otherwise be tending to close. This outcome in and of itself raises concern in my mind and is the first reason to give me reason to pause before adopting this practice.

Aside from the societal issues these families face and the problems their infants experience, the swelling volume of patients NICUs have to contend with are quite simply overwhelming resources with time. Although I reside in Canada, it is the trend shown that likely motivated some states to adopt such a draconian approach to these mother-infant dyads.

Aside from the societal issues these families face and the problems their infants experience, the swelling volume of patients NICUs have to contend with are quite simply overwhelming resources with time. Although I reside in Canada, it is the trend shown that likely motivated some states to adopt such a draconian approach to these mother-infant dyads. where a mother could conceivably take a medication that she is unaware is on a list of “banned substances”. What about Naturopathic or herbal supplements that might test positive?

where a mother could conceivably take a medication that she is unaware is on a list of “banned substances”. What about Naturopathic or herbal supplements that might test positive?

By achieving such blockade the breakdown of heme to carbon monoxide and biliverdin (the precursor of bilirubin) is inhibited. In so doing, the production of bilirubin is reduced making one less dependent on phototherapy to rid the body of elevated levels. So simple and as you might imagine a good reason for there to have been significant interest in the product. One article by Martinez et al entitled

By achieving such blockade the breakdown of heme to carbon monoxide and biliverdin (the precursor of bilirubin) is inhibited. In so doing, the production of bilirubin is reduced making one less dependent on phototherapy to rid the body of elevated levels. So simple and as you might imagine a good reason for there to have been significant interest in the product. One article by Martinez et al entitled

This was very nicely described by Nassim Taleb and described the human trait to react to unusual events with extreme reactions. An example is no one wanting to fly in the months after the world trade centre bombing when statistically this may have been the safest period in history to fly. Similarly, we as a team need to avoid the extreme reaction of saying that we should not be resuscitating such small infants when a bad outcome occurs. As I have told many people, we know these patients will not all survive, we know a significant number will have adverse development yet not all will and at least in our small sample thus far the babies would appear to be doing better overall than anticipated. If we know that bad outcomes will occur then why do we hear the questions come when they do such as “why are we doing this?”, “maybe we should rethink our position on 23 week infants”. It happens because we care and we hate seeing families and their babies go through such painful experiences. What we cannot do though for the sake of those such as our visitor today is react with a “Black Swan” reaction and steer the ship so to speak in the previous direction we were in. There are survivors and they may do well and that is why I say “Micropreemie Lives Matter”.

This was very nicely described by Nassim Taleb and described the human trait to react to unusual events with extreme reactions. An example is no one wanting to fly in the months after the world trade centre bombing when statistically this may have been the safest period in history to fly. Similarly, we as a team need to avoid the extreme reaction of saying that we should not be resuscitating such small infants when a bad outcome occurs. As I have told many people, we know these patients will not all survive, we know a significant number will have adverse development yet not all will and at least in our small sample thus far the babies would appear to be doing better overall than anticipated. If we know that bad outcomes will occur then why do we hear the questions come when they do such as “why are we doing this?”, “maybe we should rethink our position on 23 week infants”. It happens because we care and we hate seeing families and their babies go through such painful experiences. What we cannot do though for the sake of those such as our visitor today is react with a “Black Swan” reaction and steer the ship so to speak in the previous direction we were in. There are survivors and they may do well and that is why I say “Micropreemie Lives Matter”.