by All Things Neonatal | Sep 28, 2017 | caffeine, preemie, Prematurity

Given that many preterm infants as they near term equivalent age are ready to go home it is common practice to discontinue caffeine sometime between 33-34 weeks PMA. We do this as we try to time the readiness for discharge in terms of feeding, to the desire to see how infants fare off caffeine. In general, most units I believe try to send babies home without caffeine so we do our best to judge the right timing in stopping this medication. After a period of 5-7 days we generally declare the infant safe to be off caffeine and then move on to other issues preventing them from going home to their families. This strategy generally works well for those infants who are born at later gestations but as Rhein LM et al demonstrated in their paper Effects of caffeine on intermittent hypoxia in infants born prematurely: a randomized clinical trial., after caffeine is stopped, the number of intermittent hypoxic (IH) events are not trivial between 35-39 weeks. Caffeine it would seem may still offer some benefit to those infants who seem otherwise ready to discontinue the medication. What the authors noted in this randomized controlled trial was that the difference caffeine made when continued past 34 weeks was limited to reducing these IH events only from 35-36 weeks but the effect didn’t last past that. Why might that have been? Well it could be that the babies after 36 weeks don’t have enough events to really show a difference or it could be that the dose of caffeine isn’t enough by that point. The latter may well be the case as the metabolism of caffeine ramps up during later gestations and changes from a half life greater than a day in the smallest infants to many hours closer to term. Maybe the caffeine just clears faster?

Follow-up Study attempts to answer that very question.

Recognizing the possibility that levels of caffeine were falling too low after 36 weeks the authors of the previous study begun anew to ask the same question but this time looking at caffeine levels in saliva to ensure that sufficient levels were obtained to demonstrate a difference in the outcome of frequency of IH. In this study, they compared the original cohort of patients who did not receive caffeine after planned discontinuation (N=53) to 27 infants who were randomized to one of two caffeine treatments once the decision to stop caffeine was made. Until 36 weeks PMA each patient was given a standard 10 mg/kg of caffeine case and then randomized to two different strategies. The two dosing strategies were 14 mg/kg of caffeine citrate (equals 7 mg/kg of caffeine base) vs 20 mg/kg (10 mg/kg caffeine base) which both started once the patient reached 36 weeks in anticipation of increased clearance. Salivary caffeine levels were measured just prior to stopping the usual dose of caffeine and then one week after starting 10 mg/kg dosing and then at 37 and 38 weeks respectively on the higher dosing. Adequate serum levels are understood to be > 20 mcg/ml and salivary and plasma concentrations have been shown to have a high level of agreement previously so salivary measurement seems like a good approach. Given that it was a small study it is work noting that the average age of the group that did not receive caffeine was 29.1 weeks compared to the caffeine groups at 27.9 weeks. This becomes important in the context of the results in that earlier gestational age patients would be expected to have more apnea which is not what was observed suggesting a beneficial effect of caffeine even at this later gestational age. Each patient was to be monitored with an oximeter until 40 weeks as per unit guidelines.

So does caffeine make a difference once term gestation is reached?

A total of 32 infants were enrolled with 12 infants receiving the 14 mg/kg and 14 the 20 mg/kg dosing. All infants irrespective of assigned group had caffeine concentrations above 20 mcg/mL ensuring that a therapeutic dose had been received. The intent had been to look at babies out to 40 weeks with pulse oximetry even when discharged but owing to drop off in compliance with monitoring for a minimum of 10 hours per PMA week the analysis was restricted to infants at 37 and 38 weeks which still meant extension past 36 weeks as had been looked at already in the previous study. The design of this study then compared infants receiving known therapeutic dosing at this GA range with a previous cohort from the last study that did not receive caffeine after clinicians had determined it was no longer needed.

The outcomes here were measured in seconds per 24 hours of intermittent hypoxia (An IH event was defined as a decrease in SaO2 by ⩾ 10% from baseline and lasting for ⩾5 s). For graphical purposes the authors chose to display the number of seconds oxygen saturation fell below 90% per day and grouped the two caffeine patients together given that the salivary levels in both were therapeutic. As shown a significant difference in events was seen at all gestational ages.

Putting it into context

The scale used I find interesting and I can’t help but wonder if it was done intentionally to provide impact. The outcome here is measured in seconds and when you are speaking about a mean of 1200 vs 600 seconds it sounds very dramatic but changing that into minutes you are talking about 20 vs 10 minutes a day. Even allowing for the interquartile ranges it really is not more than 50 minutes of saturation less than 90% at 36 weeks. The difference of course as you increase in gestation becomes less as well. When looking at the amount of time spent under 80% for the groups at the three different gestational ages there is still a difference but the amount of time at 36, 37 and 38 weeks was 229, 118 and 84 seconds respectively without caffeine (about 4, 2 and 1 minute per day respectively) vs 83, 41, and 22 seconds in the caffeine groups. I can’t help but think this is a case of statistical significance with questionable clinical significance. The authors don’t indicate that any patients were readmitted with “blue spells” who were being monitored at home which then leaves the sole question in my mind being “Do these brief periods of hypoxemia matter?” In the absence of a long-term follow-up study I would have to say I don’t know but while I have always been a fan of caffeine I am just not sure.

Should we be in a rush to stop caffeine? Well, given that the long term results of the CAP study suggest the drug is safe in the preterm population I would suggest there is no reason to be concerned about continuing caffeine a little longer. If the goal is getting patients home and discharging on caffeine is something you are comfortable with then continuing past 35 weeks is something that may have clinical impact. At the very least I remain comfortable in my own practice of not being in a rush to stop this medication and on occasion sending a patient home with it as well.

by All Things Neonatal | Mar 14, 2015 | caffeine

If that is not a title designed purely to gather attention I don’t know what is. I can’t take credit for the title thought as I borrowed it from the following video and article link. . In late 2014 and January of 2015 the subject of using these two medications to improve survival without chronic lung disease-CLD (for a review see here) started making the rounds of many websites and news agencies.

Caffeine is given to premature infants to stimulate breathing via blockade of adenosine receptors in the brainstem. As adenosine inhibits breathing in this part of the brain it is an effective treatment to address apnea in the newborn. In 2006 Schmidt B et al published the Caffeine For Apnea of Prematurity (CAP) Trial (Full Article) and demonstrated that infants 500 – 1250g who received caffeine versus those who did not, spent less time on a ventilator and furthermore had less chronic lung disease in the long run. A win on both fronts and in essence established early caffeine use as a standard therapy in NICUs. Further research has demonstrated that early use of caffeine has other benefits when given shortly after delivery such as fewer intubations, greater success supporting infants using CPAP alone rather than invasive ventilation. Although many mother’s around the world avoid caffeine during pregnancy it has become one of the most common drugs used in the premature newborn and to allay any anxiety about outcome, a follow-up study from the CAP study above has shown no harm in long-term neurodevelopment from the exposure to caffeine.

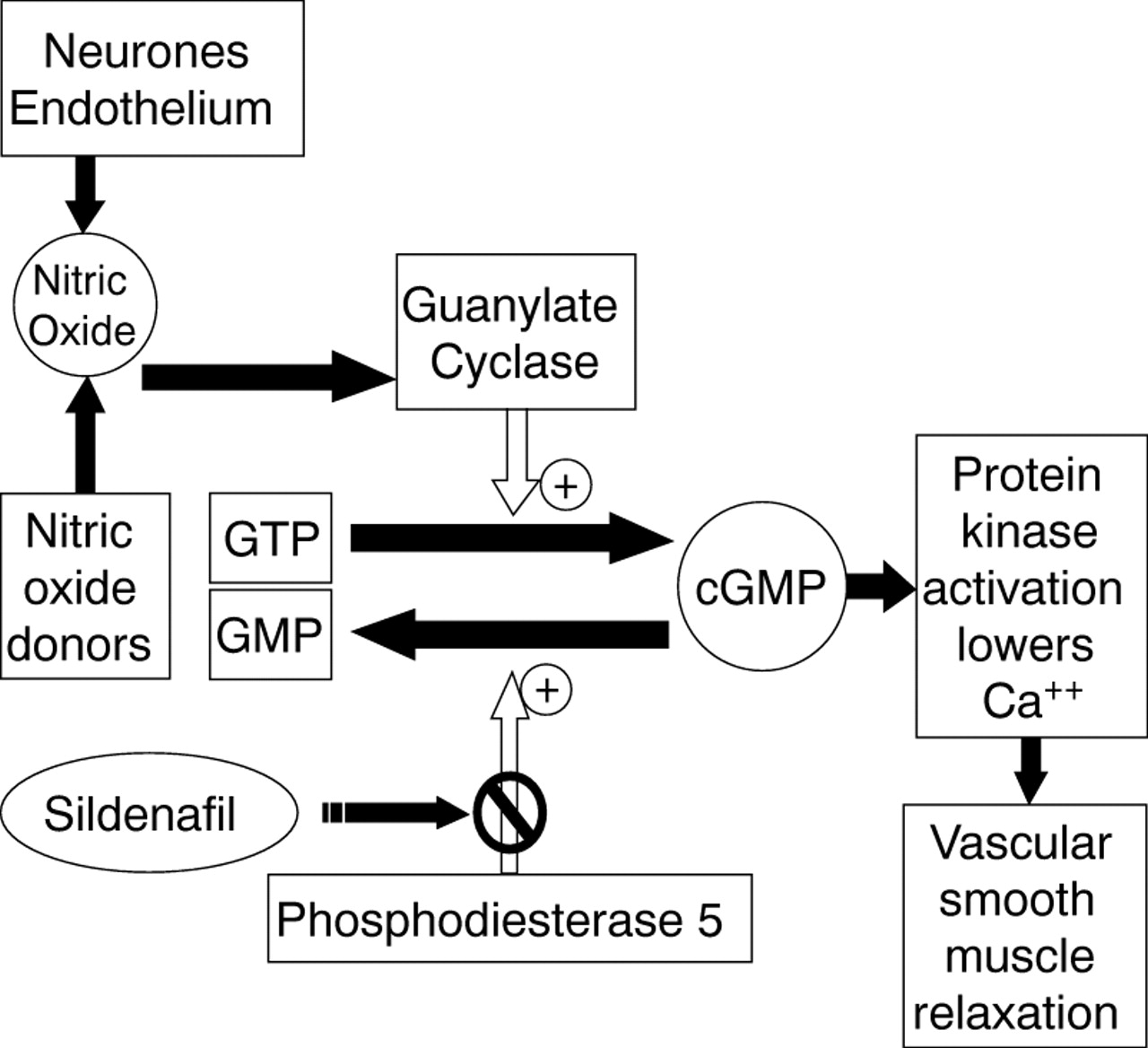

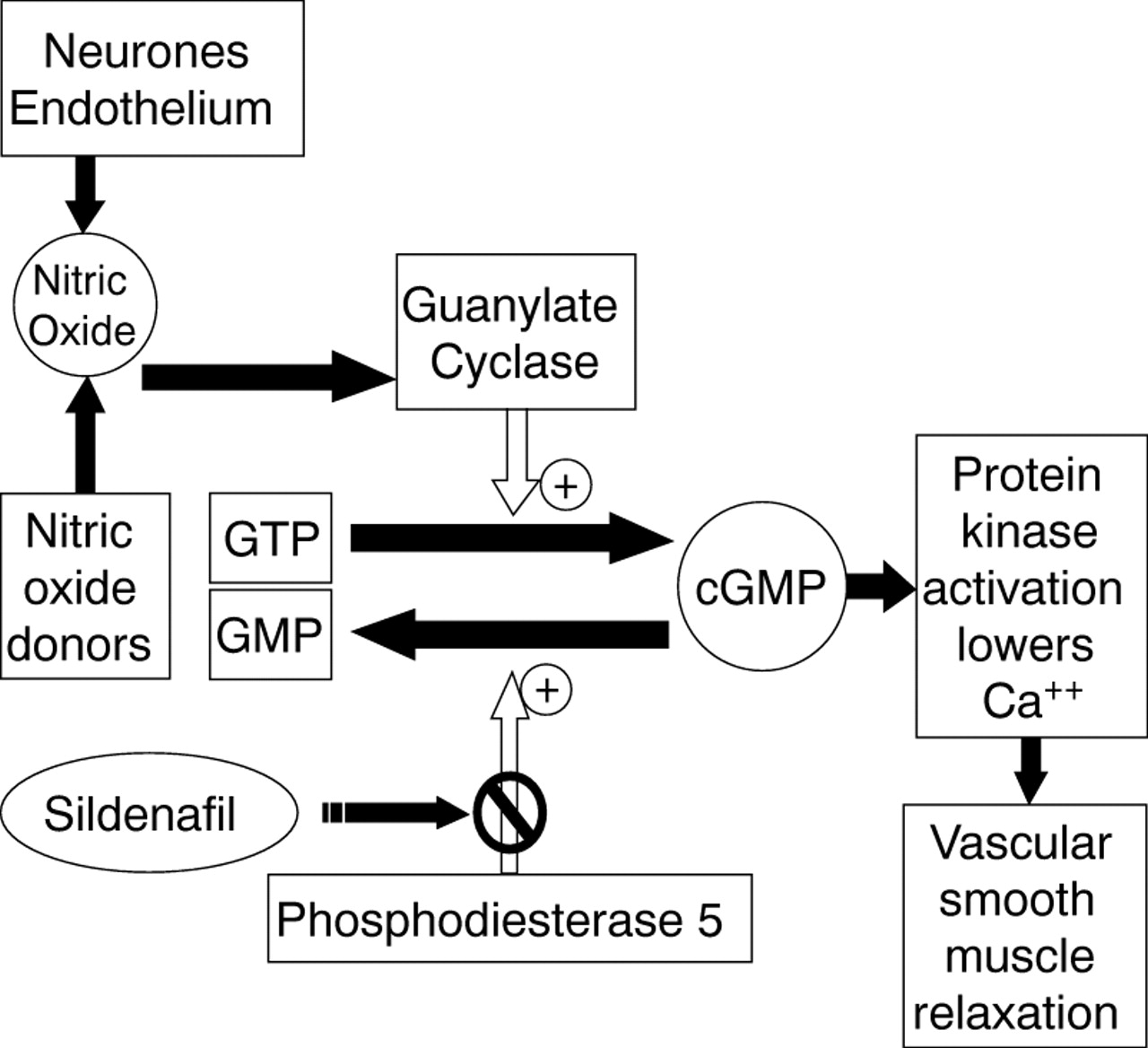

What then about Sildenafil otherwise known by it’s trade name Viagra? Sildenafil is a phosphodiesterase V inhibitor which works by increasing levels of cGMP which in turn cause the smooth muscle in arterial vessels to relax.

It may surprise some of you to learn that Sildenafil was originally designed to treat high blood pressure in the lungs or pulmonary hypertension. It was a well-known side effect that took it’s marketing in a completely different direction. Previous research however, studying the impact on patients with pulmonary hypertension in the newborn demonstrated that sildenafil alone or in combination with inhaled nitric oxide could reduce pulmonary vasoconstriction. Approximately 10-25% of premature infants with CLD have accompanying pulmonary hypertension depending on how one defines it’s presence. Sildenafil then could arguably be used to treat patients who have established CLD or perhaps even evolving CLD to prevent the oxygenation problem from pulmonary hypertension that accompanies CLD.

“Save your preemie with Caffeine and Viagra!” seems to indicate that the evidence is out there and that it is VERY positive but sadly it just isn’t. The evidence for use of sildenafil in established CLD is weak and limited to small observational or retrospective studies in which patients were put on long-term sildenafil and over time improved. The challenge with these types of studies is that it is difficult to say with any certainty that the patient wouldn’t have improved over many months anyway. Certainly, in those reports where the medication was stopped and ultrasound evidence of pulmonary hypertension returned, it is suggestive but these one-off cases are not enough to convince me that it should be considered as a standard of care.

Rat models of evolving CLD have demonstrated improved angiogenesis and alveolar growth with additional findings in the heart of less right ventricular enlargement and pulmonary hypertension. If confirmed in humans this would certainly be a wonderful treatment to prevent CLD from developing, as these findings are largely what contribute to this diagnosis. So what is the evidence for a preventative effect of sildenafil?

One Tiny RCT

In this study of 20 patients, half were randomized to sildenafil 3 mg/kg/d and half to placebo for a 4 week course starting at day 7 of age in patients who were still ventilated. In the end only 7 patients in the sildenafil arm finished the study. No differences in any outcomes were found so no benefit could be demonstrated. The study was underpowered to find a difference and aside from that the dose chosen was low compared to other studies using as much as 8 mg/kg/d. Could a larger dose shown a difference in outcome? Maybe but again a larger sample size would have helped and I suspect will come with time. The bottom line is that it was a small study that does not add anything to the pool of evidence suggesting a benefit of sildenafil in either treatment of patients with CLD or to prevent it.

This is the danger of course in the lay press hearing about information like this. It is sensational and will attract a lot of readers but in the end should parents be asking their health care providers in NICU to use sildenafil as a standard treatment for CLD or to prevent it? For the time being I would say not but with the provision that I actually believe there may be a role but for the right patient.

In our unit we have an Integrated Targeted Neonatal Echocardiography program that allows us to take measurements of pulmonary vascular resistance that are quite different from traditional measures reported using a standard echocardiogram. Using this technique, patients with pulmonary hypertension can be identified and treated whether it be with inhaled nitric oxide or sildenafil or both. It is also tempting to speculate that there may be early predictors of patients who may develop CLD with pulmonary hypertension and it is those premature infants that would like be the best to target such therapies in. By selecting out those patients only who would develop this condition a therapy to prevent it would be better studied in a pure sample. Treating the 75-90% of patients who will not develop this condition with a drug will dilute out your results for sure compared to studying only those patients with a high likelihood of disease. I will have to dream of this type of study for the time being though as I am unaware of such work being done at the moment.

Finally I think it is worth mentioning that Sildenafil should not be used without some caution. In 2012 the US FDA issued a warning (read warning here) on the use of high doses of Sildenafil for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension due to a higher mortality rate in a Pediatric clinical trial (Free article here) involving children at least a year of age. The high dose group received a dose from roughly 3-6 mg/kg/day which is in keeping with the dosing used in the trials in infants. Since that time the FDA has softened it’s stance (clarification) but it need to be acknowledged that the use of Sildenafil under a year of age is considered off label and with the aforementioned concerns it would seem prudent if using the medication to use a lower dose.

Taking all of this information in I would suggest it seems wise to continue giving our premature infants a morning cup of coffee each day but for the time being I would leave more frequent use of Viagra to the adults.