I have written a number of times already on the topic of dextrose gels. Previous posts have largely focused on the positive impacts of reduction in NICU admissions, better breastfeeding rates and comparable outcomes for development into childhood when these gels are used. The papers thus far have looked at the effectiveness of gel in patients who have become hypoglycemic and are in need of treatment. The question then remains as to whether it would be possible to provide dextrose gel to infants who are deemed to be at risk of hypoglycemia to see if we could reduce the number of patients who ultimately do become so and require admission.

I have written a number of times already on the topic of dextrose gels. Previous posts have largely focused on the positive impacts of reduction in NICU admissions, better breastfeeding rates and comparable outcomes for development into childhood when these gels are used. The papers thus far have looked at the effectiveness of gel in patients who have become hypoglycemic and are in need of treatment. The question then remains as to whether it would be possible to provide dextrose gel to infants who are deemed to be at risk of hypoglycemia to see if we could reduce the number of patients who ultimately do become so and require admission.

Answering that question

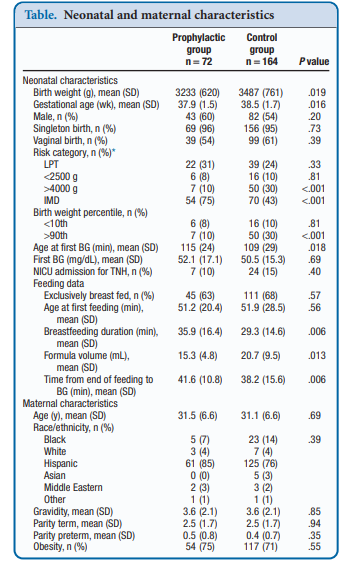

Recently, Coors et al published Prophylactic Dextrose Gel Does Not Prevent Neonatal Hypoglycemia: A Quasi-Experimental Pilot Study. What they mean by Quasi-Experimental is that due to availability of researchers at off hours to obtain consent they were unable to produce a randomized controlled trial. What they were able to do was compare a group that had the following risk factors (late preterm, birth weight <2500 or >4000 g, and infants of mothers with diabetes) that they obtained consent for giving dextrose gel following a feed to a control group that had the same risk factors but no consent for participation. The protocol was that each infant would be offered a breastfeed or formula feed after birth followed by 40% dextrose gel (instaglucose) and then get a POC glucose measurement 30 minutes later. A protocol was then used based on different glucose results to determine whether the next step would be a repeat attempt with feeding and gel or if an IV was needed to resolve the issue.

To be sure, there was big hope in this study as imagine if you could prevent a patient from becoming hypoglycemic and requiring IV dextrose followed by admission to a unit. Sadly though what they found was absolutely no impact of such a strategy. Compared with the control group there was no difference in capillary glucose after provision of dextrose gel (52.1 ± 17.1 vs 50.5 ± 15.3 mg/dL, P = .69).  One might speculate that this is because there are differing driving forces for hypoglycemia and indeed that was the case here where there were more IDMs and earlier GA in the prophylactic group. On the other hand there were more LGA infants in the control group which might put them at higher risk. When these factors were analyzed though to determine whether they played a role in the lack of results they were found not to. Moreover, looking at rates of admission to the NICU for hypoglycemia there were also no benefits shown. Some benefits were seen in breastfeeding duration and a reduction in formula volumes consistent with previous studies examining the effect of glucose gel on both which is a win I suppose.

One might speculate that this is because there are differing driving forces for hypoglycemia and indeed that was the case here where there were more IDMs and earlier GA in the prophylactic group. On the other hand there were more LGA infants in the control group which might put them at higher risk. When these factors were analyzed though to determine whether they played a role in the lack of results they were found not to. Moreover, looking at rates of admission to the NICU for hypoglycemia there were also no benefits shown. Some benefits were seen in breastfeeding duration and a reduction in formula volumes consistent with previous studies examining the effect of glucose gel on both which is a win I suppose.

It may also be that when you take a large group of babies with risks for hypoglycemia but many were never going to become hypoglycemic, those who would have had a normal sugar anyway dilute out any effect. These infants have a retained ability to produce insulin in response to a rising blood glucose and to limit the upward movement of their glucose levels. As such what if the following example is at work? Let’s say there are 200 babies who have risk factors for hypoglycemia and half get glucose gel. Of the 100 about 20% will actually go on to have a low blood sugar after birth. What if there is a 50% reduction in this group of low blood sugars so that only 10 develop low blood glucose instead of 20. When you look at the results you would find in the prophylaxis group 10/100 babies have a low blood sugar vs 20/100. This might not be enough of a sample size to demonstrate a difference as the babies who were destined not to have hypoglycemia dilute out the effect. A crude example for sure but when the incidence of the problem is low, such effects may be lost.

A Tale of Two Papers

This post is actually part of a series with this being part 1. Part 2 will look at a study that came up with a different conclusion. How can two papers asking the same question come up with different answers? That is the story of medicine but in the next part we will look at a paper that suggests this strategy does work and look at possible reasons why.

Be great to get Jane Harding to write a commentary on this.

would welcome her expert opinion